The trajectory of human history has changed from isolation to one that is increasingly integrated (Hou, 2017). The globally interconnected world that has emerged as a result of this integration has had significant impacts on many aspects of people’s lives across the globe (Spring & Zhao, 2010). For example, economic integration, cultural integration and political integration are all products of globalisation. Pursuant to this trend across the whole of society, globalisation has gained importance as a research paradigm in pedagogy theory, and the overall trend in global education also reflects this tendency of integration (Wu, 2003).

Educational integration is mainly reflected in education policies, thematic documents, proposals, reports, and documents issued by international organisations at international conferences, which form international policies, expand within the global context, and guide the direction of the development of global education (Sheng, 2011, p. 5). They define the direction of global education from the superstructure (Smith, 2003). An early example of this is an article entitled ‘The need for global education’ by Robert Muller, was published in the New Era, a British journal. In this article, Muller argues that a global approach to education is required to prepare children properly for the world of tomorrow (Muller, 1990), proposing a ‘World Core Curriculum’. The framework of this ‘World Core Curriculum for Global Education’ consisted of four parts:

-

Our planetary home and place in the universe;

-

Our place in time;

-

The family of humanity; and

-

The miracle of individual life (Muller, 1998).

The main purpose of this global framework was to guide the world’s educators on what should be taught in schools across the world (Muller, 1989).

Muller’s ideas were highly valued in the educational sector, and since then have been recognised and promoted by the United Nations’ Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). In this way, the ‘global education’ and the ‘global knowledge’ framework have been gradually recognised the world over. The latter offers several advantages, such as opening children’s eyes to realities, exposing children to various cultures, ensuring children have global mindsets and appreciation for the world at large, and preparing them to become good global citizens. Indeed, many education systems require teachers to address these competencies which are ‘globally oriented’. A pertinent example is the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) – it has involved more than 90 countries and economies worldwide since 2000 (OECD, 2022). Many countries design their curriculum frameworks according to the PISA questionnaire.

However, education systems also need to consider that all countries have different ethnic cultures, historical backgrounds, national spirits, ways of thinking, and value systems. If nations limit the curriculum structures to focus solely on international frameworks and ignore local resources and factors, students will become world citizens but their national belonging and sense of identity will gradually become confused (Han, 2013, p. 7).

To overcome this concern, some nations, including China, while advocating ‘global knowledge’, have constructed curriculum that also celebrates and acknowledges local cultures, providing opportunities for children to learn about their unique cultural characteristics. These countries focus on cultivating global citizens while also attaching importance to the cultivation of local cultures. They try to strike a balance between global and national citizenship by paying attention to developing students’ sense of belonging to the local culture, while also developing a rational attitude about the relationship between their country and the world at large (Rao, 2018).

With this perspective in mind, the Chinese government not only advocates for students to become global citizens but has also paid close attention to the importance of local culture in education. This is evidenced by the government having recently published a document entitled: ‘The Implementation of the Inheritance and Development Project of Chinese Excellent Traditional Culture’, which advocates for schools to educate students about Chinese culture throughout national education. It notes:

Educators at every stage, including enlightenment, basic, vocational, higher, and continuing education had better integrate the excellent traditional Chinese culture into all aspects of ideological, moral, cultural knowledge, art, and physical and social practice education. We would like to build a Chinese culture curriculum and textbook system focusing on textbooks for children in primary and middle school (People’s Republic of China State Council, 2017).

This response suggests that, after experiencing the impact of globalisation and promoting the younger generation’s global abilities, including speaking English, the government has realised that its own national languages and cultural traditions must also be treasured (Zhou, 2021).

Based on this, educators have in recent years gradually begun to carry out educational activities focused on Chinese traditional culture, with the aim of raising the cultural consciousness and self-confidence of its people (Yang, 2021). This is especially the case in the preschool stage, which is when children first engage in systematic education (Chen & Liu, 2019). As early as 2001, the ‘Guiding outline for kindergarten education’, issued by the Ministry of Education of Mainland China, stipulated that ‘children should be guided to feel the richness and excellence of the motherland’s culture’ (Ministry of Education, 2001). This focus suggests that preschool teachers have a responsibility to integrate Chinese traditional culture into preschool education so that children grow up with a sense of identity and belonging to their own culture and country (Yang, 2021).

In support of this approach, Wang (2019) has proposed that, given the influence of Western globalism, people should be more aware of the importance, value, and significance of establishing their national identity and citizenship. To achieve this goal, culture is seen as a decisive force (Laszlo, 1972), with traditional festivals portraying Chinese national spirit and morality. In this way, one important function of traditional festival activities in schools is to promote children’s understanding of traditional culture (Zeng & Wang, 2018).

However, children aged 3–6 years often struggle to understand the complex cultural connotations of culture through traditional didactic teaching methods. Innovative ways are therefore needed in order to help children internalise the essence of that knowledge. Davis (2014), a drama educator, notes that drama strategies offer one means of opening up new spaces for children to engage with culture. Similarly, Bolton (1979) noted that drama can help students understand the world.

This paper is therefore focused on examining a project designed to determine the effectiveness of using drama education strategies to gain a deeper appreciation of their strong cultural heritage through traditional festivals. It took the Mid-Autumn Festival as an example of a traditional festival, with the drama work being presented to children in kindergarten. The paper aims to determine the value of drama activities for children, discusses the challenges in this teaching approach, and provides some suggestions for future action by kindergarten teachers who have an interest in applying this approach.

The Mid-Autumn Festival

The Mid-Autumn Festival is a traditional festival in China. It is also known as the moon festival because it originated from the ancient worship of the moon in Autumn. Offering the moon a sacrifice is an ancient custom associated with this festival. In ancient times, people set up large tables with incense and performed sacrificial rites, offering watermelons, apples, red dates, pomegranates, and the memorial tablet of the ‘moon god’, which they used to express people’s good wishes and prayers for blessings. As the Festival takes place during the full moon and the shape symbolises the full cycle in the Mid-Autumn Festival, the moon is considered to symbolise perfection, completeness, and reunion. As such, the Chinese consider the full moon a representation of the reunion of families, with the Mid-Autumn Festival symbolising humanistic care, profound cultural connotations, and the traditional cultural spirit of peace. For Chinese people, family harmony represents the perfect form of human relations, and so at this time, people commonly desire family reunions (Huang & Sun, 2018).

Eating moon cakes is one of the most important customs of the Mid-Autumn Festival. The moon cakes are round, like the full moon, and many Chinese people like to send them to relatives and friends as a symbol of reunion, harmony, and beauty. Many traditional fairy tales are also associated with the Mid-Autumn Festival, including the ‘Goddess Change Flying to the Moon’, ‘The Archer and the Suns’, and the ‘Moon Rabbit Grinding Medicine’. Within these stories, Change and Hou Yi are the most popular mythical characters, with most stories including them in order to convey a sense of longing for family reunions.

Research Methodology

Case Study

The case study as a methodology fits drama education well, because participation in drama education creates a unique set of social relationships that become a single unit of experience capable of analysis (Carroll, 1996, p. 77). Yin emphasised that if researchers are unable to participate in the whole programme, it can be examined best by means of a case study methodology (Yin, 2013).

The purpose of this study is to identify the value of drama-based pedagogy to support kindergarten children’s understanding of traditional Chinese festivals and their significance. Within this case study, the author did not intervene in any of the drama activities, including the participants’ education, curriculum design, and teaching practice, but rather, adopted the role of participant observer/observer (Yin, 2013).

Participants

Drama education was introduced to Mainland China in the 1980s. Researchers such as Professor Zhang from Beijing Normal University (Zhuhai) promoted it in the ensuing years, illustrating a drama condition named ‘Growing Drama Education’. It was proposed in 2017 and based on Chinese children’s characters. Drama education in Mainland China entered an era of local transformation in that year. However, the development in various regions took place at an uneven pace, with kindergarten teachers from Beijing, the Pearl River Delta and the Yangtze River Delta being much more likely to accept the theories of drama education, having extensive teaching experience of drama education.

The participants for this study were therefore identified through purposive sampling, with the participating preschool teachers being selected based on their extensive experience in drama education and ability to design lessons which were focused on Chinese traditional festivals. The research team involved in this study has been engaged in studying preschool drama education for several years and thus had the advantage of finding suitable research participants from the said regions.

With this background in mind, a kindergarten school in Guangdong province was selected. This province has retained many distinctive local customs around the Mid-Autumn Festival - not just eating moon cakes and admiring the full moon, but through activities such as flying the Kong Ming lantern, guessing lantern riddles, making lanterns with shaddock peels, submitting offerings to ancestors, and eating taros, pomegranates, and groundnuts. When the Mid-Autumn Festival approaches, cities across Guangdong province hang lanterns and coloured lights on trees by the roadside to usher in a festive atmosphere.

In terms of the teacher participant, at the time of this study, Teacher C, taught a class of children aged 5-6 years, and had been working as a kindergarten teacher for about 30 years. From 2013 onward, she began participating in international drama education conferences and workshops organised by international and local drama scholars. She underwent drama education training for kindergartens and was honoured as a Special-grade Teacher of Drama Education at kindergarten level. As such, she had considerable experience organising activities using drama pedagogies.

There were 30 children (17 girls, 13 boys) in her class. Some had an initial understanding of the Mid-Autumn Festival, but none of the children had a strong grasp of the importance and meaning of this Festival within traditional Chinese culture. Across the research period, Teacher C was observed by the author in order to ascertain how she organised activities around the Mid-Autumn Festival, including how she used drama-based pedagogy to improve the children’s understanding of the meaning of and emotions around this Festival. She organised three educational drama activities related to the festival, with each activity lasting about 40 minutes.

Data Collection and Analysis

The data were gathered through interviews, observation of activities, documented reports of activities, and the teacher’s reflections. Before entering the classroom to observe drama-related activities of the Mid-Autumn Festival, the researcher interviewed the teacher participant, with the main purpose being to learn about the lesson designs and teaching objectives.

As kindergarten teachers are fully engaged with their responsibilities and have to conscientiously take care of the children in their classes, it was difficult to schedule a fixed interview time with Teacher C. The semi-structured interviews were therefore conducted during Teacher C’s spare time. Documents relating to the series of drama lessons, including her activity designs, mind maps, teaching network diagrams, weekly plans, etc. were also collected. These enabled the researchers to gain a thorough understanding of Teacher C’s educational concepts and drama activities related to the festival.

The lead researcher also observed Teacher C in her classroom while she was conducting drama-based activities related to the Mid-Autumn Festival. Following these lessons, the researcher interviewed Teacher C to discuss the actions observed. More targeted interview data were subsequently collected, which supplemented the interview data drawn from the previous stage, and which served to validate the observational data. The interviews and activities were recorded, filmed, and photographed for purposes of data analysis. Data collection and analysis took place simultaneously. The researcher transcribed, coded, and analysed the data simultaneously, continuously, and circularly, in order to accurately analyse the data and summarise the findings. The datasets were triangulated (Auerbach & Silverstein, 2003), which means that different data were corrected and compared to improve research authenticity. The coding categories used in the study are presented in Table 1.

Ethics

Ethical consideration was given to the lead researcher’s relationship with their participants and for being responsible for the research texts and data. All of data were subject to responsible and ethical conduct standards. Before collecting data, the consent of the kindergarten leaders, Teacher C and all the children’s parents was obtained, with a key component for consent being that all electronic data would be stored on a private computer, and not used for commercial purposes. Children’s portraiture rights were also protected.

Overview of the Lesson Sequence

Following the success of the Apollo Programme in the 1960s, the first human landed on the moon in 1969. This event inspired people’s enthusiasm for investigating the moon. During the following 50 years, exploration of the moon became a global endeavour. Many countries launched programmes of exploration, such as India’s ‘Chandrayaan-3’, Israel’s ‘Beresheet 2’, and China’s ‘Change Program’. The moon came to symbolise science and technology, and an increasing number of people associated the moon with space exploration (Xiao, 2012). Given these global influences, Chinese people’s traditional concepts and consciousness of the moon seemed to gradually fade.

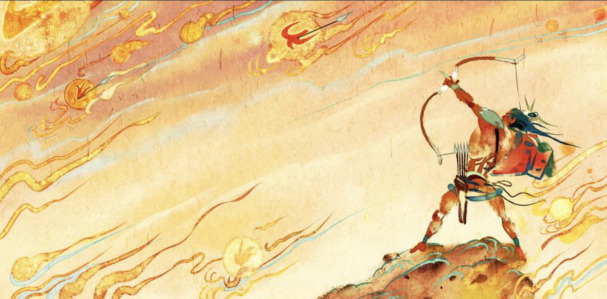

In order to establish the nexus between the moon and children’s cultural identity, Teacher C set up activities around the moon and the festival, using drama pedagogy. On the first day, the teacher started with two representative characters related to the Mid-Autumn Festival: Hou Yi and Change, and selected two typical pictures, such as those seen in Figures 1 and 2, namely ‘Hou Yi Shooting the Sun’ and ‘Change Flying to the Moon’. Teacher C wrote in her reflections:

I must choose Chinese factors to start class. Change and Hou Yi are the most representative local characters of the moon and the Mid-Autumn Festival. They are in sharp contrast to the lunar landing project that countries across the world are focusing on. I can lead children to experience national feelings around the moon, which can help cultivate their sense of cultural belonging’ (LP20210915).

Teacher C then guided the children to create a story on Hou Yi and Change entirely through conversation using three steps:

-

Teacher C asked the children what they could see in the picture.

-

Teacher C asked the children what the characters in the picture were doing.

-

Teacher C had a conversation with the children about why the people in the picture did what they were doing.

For example, when Teacher C presented Figure 2, the following conversation ensued:

Teacher C: What can you see in the picture?

Child 2: She is flying to the sky.

Teacher C: Why is she flying to the sky?

Child 8: She drank the elixir, otherwise this elixir may be stolen by Hou Yi’s apprentice, a bad man.

Teacher C: Is Change willing to drink this elixir?

Child 12: No.

Teacher C: Why not?

Child 6: Because she is crying.

Child 2: Because she is looking at Hou Yi who is standing on the ground.

Child 9: Hou Yi is also crying.

Teacher C: Yes, they are all crying. Why is Hou Yi crying?

Child 11: Change is his wife, and she will leave him forever to protect the elixir for Hou Yi.

Teacher C: How do they feel?

Child 21: They are very sad.

Child 29: They do not want to leave each other.

Teacher C: What will they say to each other?

No response for about 30 seconds.

Children: Do not leave! (OR20210915).

After a long discussion, Teacher C helped the children understand the characters and their different roles and created a story context around Hou Yi and Change. This storyline revealed that Change and Hou Yi were a couple. Change worked as a weaver and cooked at home every day, while Hou Yi helped villagers fight a beast. One day, 10 suns appeared in the sky, and all the villagers suffered from the heat. Hou Yi shot down the extra suns. Yu Ti therefore gave Hou Yi two elixirs to help him and Change become immortal. They made an appointment to drink the elixir together on the night of the full moon during the Mid-Autumn Festival, and to become gods together. However, one day, one of Hou Yi’s disciples wanted to grab the two elixirs when Hou Yi left home. To prevent the elixir from falling into the disciple’s hands, Change quickly drank them both. When Hou Yi got home, he saw Change cry as she flew away (OR20210915).

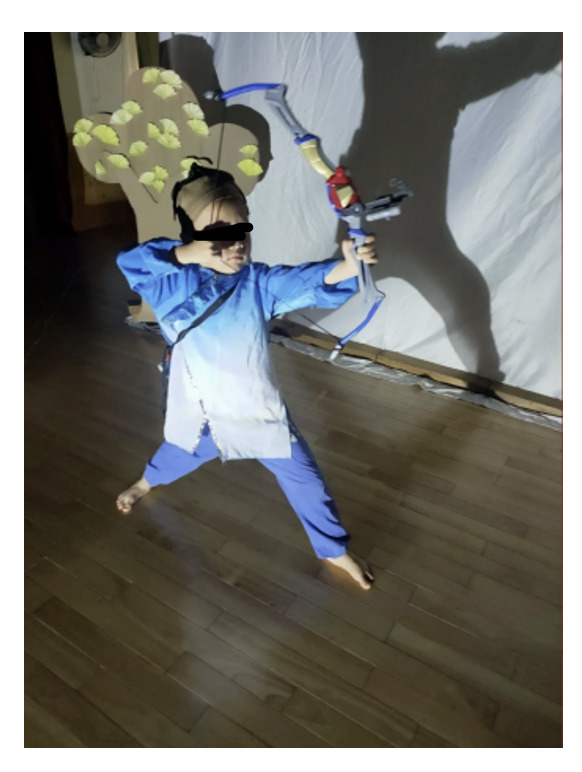

On the second day, Teacher C suggested that all the children participate in bringing the story to life and helped them review the storyline through the ‘story circle’ convention. In this process, Teacher C dictated the story created by children in the first-day activity and created the drama situation for children. With Teacher C’s guidance, every child had the chance to experience all characters and the storyline following teachers’ instructions. In Figure 3 and Figure 4, for example, children followed the teachers’ instructions to pretend to be Hou Yi shooting the sun.

After the ‘story circle’ convention, Teacher C divided this story into three parts, and she transferred the teaching place from the classroom to the children’s theatre outside (see Figure 5). In this theatre, children chose their favourite characters and dressed up. These children then had more chances to embody and experience the entire story of freedom by engaging in dramatic play as characters (OR20210916).

Following this part of the learning sequence, Teacher C wrote in her reflections: The children are more likely to forget the content of the story, even if it is created by themselves. So, in today’s drama activity, I transferred place from the classroom to the theater. In this way, every child had a chance to have an embodied experience of this story which may help them to remember and understand this story (LP20210916).

On the third day, Teacher C acted as the village head, and the children acted as the villagers. Teacher C said to the children, ‘I saw Hou Yi walking around in the village in sadness because his wife had left him. However, it is the Mid-Autumn Festival today. In our village, we celebrate the festival with our families. Hou Yi may feel lonely today. What can we do for him?’ The children suggested ideas, such as sending Hou Yi mooncakes and other traditional food. Teacher C then said, ‘These ideas are good, and there are many other traditional handmade foods that we make during the Mid-Autumn Festival. Let me tell you about them so that we can make more food for Hou Yi and go to his house for company in the evening!’

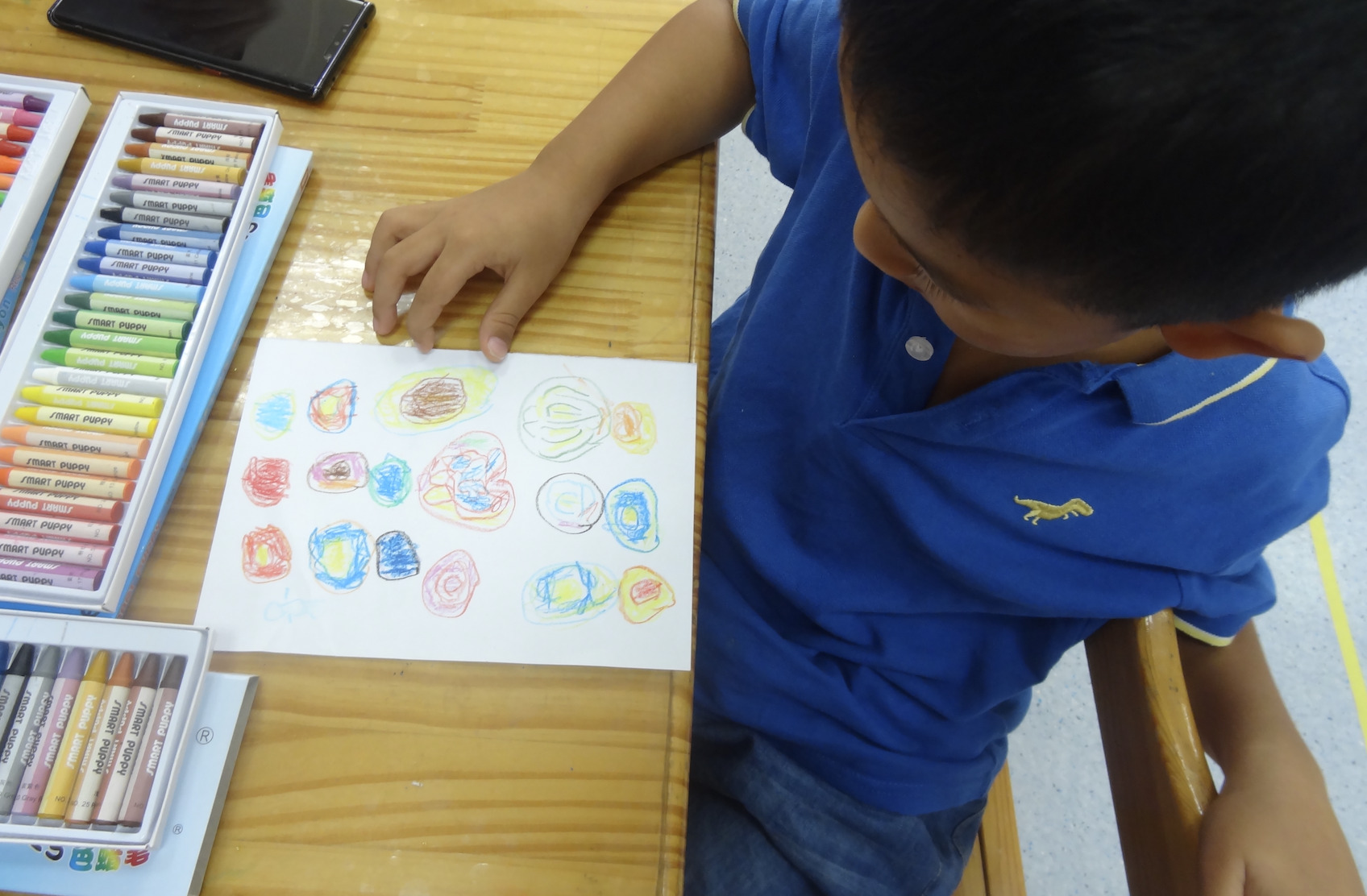

In role as the village head, Teacher C taught the children about the traditional customs around the Mid-Autumn Festival and encouraged them to make handmade products, mooncakes, Kong Ming and flower lanterns, and put them up in their classroom. Children made or painted products for Hou Yi depending on their favorite. In the whole activity, children were still in the role of villagers, and the purpose of making handmade products was to give these gifts to Hou Yi and accompany him to celebrate Mid-Autumn Festival (OR20210917).

Impact on the Students

Improving Children’s Understanding of the Story

On the first day, Teacher C led the children to express, create, and imagine their thoughts by guiding them. She relied on discussions to trigger the children’s desire to express and explain their ideas. Though the story of the Mid-Autumn Festival is quite famous in China, Teacher C did not want to use the original story plot and lead children to remember the whole story by rote. She regarded the drama activity as a constructive process. To achieve this, Teacher C chose some important roles such as Change and Hou Yi, and then triggered the children’s exploration of the characters through continuous discussions with them to construct the whole storyline. When asked why she had started her activities by analysing the characters, including Change and Hou Yi, Teacher C responded as follows:

Teacher C: The roles are the clues to the entire story. By observing the appearance, facial features, and actions of the characters in the picture, the children can begin building their cognition of the characters and lay the foundation for the establishment of dialogues and story plots. The dialogues in the traditional story are impossible for children to understand at first instance, owing to the limitations in the language ability and imagination. We must help children observe details of the people in the pictures and gain a deeper understanding of the roles by asking them questions first. After speaking to them, they revealed surprising insights. Children are less likely to encounter the pressure of memorisation when they perform the next step (TTI20210915).

On the first day of the activity, Teacher C staged activities with pictures and roles related to the story, so that the whole story was created by children in the classroom. This helped children to easily remember the different roles’ characteristics and the storyline, which formed a strong foundation for the drama activities that took place on the following two days.

Though Teacher C helped children to create a story about Mid-Autumn Festival based on two pictures on the first day, these children were less likely to understand the meaning and feeling of this story deeply. This prompted the following response from Teacher C:

In the first day, the main purpose of the activity was to create the storyline and help children get a preliminary understanding of the main characters in the story. However, I found some of them have not understood the meaning of the story about the Mid-Autumn Festival. They did not realise the pain of family separation in the Mid-autumn Festival and the meaning of this traditional Chinese festival in China (TTI20210916).

Therefore, on the second day and third day, Teacher C used drama strategies including, ‘story circle’ ‘role playing’ and ‘teacher in role’, to provide children with more opportunities to experience characters and the storyline. Because of the limitation of children’s cognitive development, when children really experience things directly, they are more likely to internalise them into their cognition. Drama-based pedagogies provide children with more opportunities and spaces to feel things directly. In this way, children can really feel the emotion and understand the meaning behind of the story in playing in role. For example, when the researcher asked Teacher C why she used drama-based pedagogies in activities, Teacher C responded as follows:

In today’s drama education activities, I helped the children repeatedly review the storyline in the classroom and theatre through ‘story circle’ and ‘role playing’. This storyline was created by themselves. In order to help them to understand the meaning and emotion of the story deeply, I provided them with more embodied experience and helped them have a deep understanding of the feeling of the story from doing directly (TTI20210916).

Improving the Children’s Understanding of the Deep Meaning Behind the Story

Piaget’s theory of cognitive development suggests that the cognition of children aged 3–6 years is in the pre-operational stage, and that those children are in the embryonic stage of representation and image thinking (P. Zhang et al., 2015). It therefore may be rather difficult for those children to comprehend the emotions and meanings in the story, as they are too abstract and go beyond their current stage of cognitive development. However, when teachers educate them on the customs around, emotional connections with, and other meanings of festivals through more detailed image of fairy tales, children are more likely to gain a better understanding thereof.

Sartre, a dramatist, said that drama situations created by teachers surround and provide us with solutions that can help us solve problems (Shi, 2006). In drama education, the drama situation is as important as ‘air’ is for a person (J. M. Zhang, 2019), and it provides children with infinite possibilities. For instance, in this study, Teacher C used drama conventions such as the ‘story circle’ on the second day, and described the storyline and created situations for the children, who acted as Hou Yi, Change, or ‘Head of the village’ in the space she had created (OR20210917). Children also assumed different identities, sometimes as members of the audience, at other times as villagers, which meant that they had the opportunity to be themselves and others at the same time. These shifts in positioning helped them explore the story from different perspectives (Davis, 2014). After the activities, Teacher C had a conversation with the children, one example being:

Teacher C: How are you feeling today?

Children F: I was almost torn apart when you said Change had left Hou Yi.

Teacher C: Why did you want to cry?

Children F: In that situation, I thought I was Change, and did not want to leave my husband, Hou Yi. I wanted to celebrate the Mid-Autumn Festival with Hou Yi (OR20210915).

In this discussion between Teacher C and the children, it is clear that some children could feel the sadness when Change left Hou Yi on the night of the Mid-Autumn Festival. They integrated their emotions and resonated with the relevant plots and characters naturally. Given this response, it seems that the selected approach enabled some of the children to truly experience the tension, excitement, and happiness conveyed by the story and to readily understand that the Mid-Autumn Festival is a time for family reunions and celebrations with their families.

Providing Children with a more Embodied Experience

The body is a general means to experience the world. As Nietzsche (1901/1968, p. 437) indicated in the book ‘The Will to Power’, for some, the body is much more amazing than the soul. His thought broke the devaluation and contempt of the body in the philosophy of consciousness and made the long-sealed body appear (Yan & Bailey, 2021). Philosopher Merleau-Ponty (1995) said: ‘The body is the vehicle of being in the world.’ He believed that the living body connects and integrates the physical body, mind, consciousness, and how we are in the world (McClelland et al., 2002). Embodied cognition researchers have taken the ‘embodied-embedded’ cognitive model as a basic framework to understand cognition and argue that people understand the world through the interactions between the body and environment. In the course of knowledge production and reproduction, the body is not the recognised object, but rather the cognitive subject, which plays an important role in constructing knowledge (Ye, 2019). This holds true especially for preschool children, given that their level of language and thinking development is limited, and the value of their body is the basic carrier to participate in educational activities. In drama education activities, the text of improvisation exists in the body, which retains and expresses the mode of discourse and behaviour (J. M. Zhang, 2019).

In this study, Teacher C discussed with children the storyline of these activities, and divided the whole story into three parts to perform. Every child in the class enjoyed an opportunity to play a role and experience the story created by themselves in the drama activities. In Figure 6, for example, Hou Yi is shooting the sun, while in Figure 7, Hou Yi and Change are pictured living a happy life. In Figure 8, Change is flying to the moon and leaving Hou Yi behind on the Mid-autumn Festival night.

When discussing this work, Teacher C said:

Though we discussed how different actors need to perform and what they need to say in different situations, I gave the children directions without specifying any details. Children are likely to have various ideas in the same situation. The purpose of the performance is to give children enough time and space to gain experience. When they performed part 3, which is Change flying to the moon alone and leaving Hou Yi on the earth on the night of the Festival, children acting Change and Hou Yi exhibited sad expressions (OR20210917).

Teacher C also described the customs and gave the children opportunities to make mooncakes. Figure 9 shows how a child is drawing various kinds of mooncakes and is preparing to make handmade mooncakes. This hands-on engagement was effective in helping the children understand the customs around the Mid-Autumn Festival.

Encountering Challenges

Although the sections above suggest that the children were more likely to have a deeper understanding of the meaning of the story and traditional customs of the Mid-Autumn Festival following the drama work, it seems from the teacher’s comments that these activities may not have been sufficient for them to build cultural identities and belonging. The following transcript offers this perspective. It is taken from an interview conducted with Teacher C after the three sets of activities:

Researcher: How do you evaluate your activities?

Teacher C: I think these serious activities around the Mid-autumn Festival using drama-based pedagogy are rather successful. Most children who display a high level of interest in this performance have a deep understanding of the customs and meaning of this traditional festival.

Researcher: What do you think could be done to improve these activities?

Teacher C: The purpose of these activities is to help them gain an understanding of the Mid-Autumn Festival, and to acquaint them with the significance of the traditional festival for the Chinese. Creating a Chinese cultural atmosphere that helps build a sense of belonging for them is a goal. However, most children in my class did not achieve the latter purpose. Cultural identity may be too abstract for them.

Researcher: Why do you say that?

Teacher C: Through children’s reactions and answers, I know that they understand the importance and meanings of this traditional festival. They know how to celebrate the Mid-Autumn Festival. But when I asked them about our country’s long history, our many other traditional festivals and cultures, and whether they were proud of being a Chinese, they kept silent. Obviously, it may be difficult for them to know the meaning of taking pride in being a Chinese (TTI20200917).

In her approach, Teacher C tried to use traditional characters, Change and Hou Yi, to attract the children’s interest and support their understanding of the Mid-Autumn festival. She also recreated a traditional festival and its cultural context through drama-based pedagogy. Thus, children’s embodied experience improved, which improved their understanding of the customs and histories of the Mid-Autumn Festival. Drama education therefore proved effective to this end.

However, the shaping of children’s cultural identity and belonging undoubtedly requires an extended program, and kindergarten teachers cannot accomplish it at one stroke. The researcher consequently holds the view that education systems should not be eager for quick success and instant benefit. Instead, Teacher C should consider integrating activities about Chinese culture by drama-based pedagogy across the children’s everyday lives. Kindergarten teachers could integrate Chinese traditional activities and drama-based pedagogy at all suitable times when children are in the kindergarten, such as in the course of admission activities in the morning, and corner activities.

Secondly, apart from the traditional Chinese festivals, kindergarten teachers could also have more choices about educational themes, such as themes about the Confucian classics. Confucianism is the foundation of, and is representative of, Chinese culture. Kindergarten teachers can integrate the classical theories and ideas throughout the whole day while the children are present, for example by means of drama games or activities. Through drama-based pedagogy, the whole kindergarten is surrounded by a rich cultural atmosphere, which may help children develop their cultural belongings and confidence gradually in this global world.

Conclusion

Traditional festivals are the cultural accumulation and historical background of thousands of years, and the deep driving force for the inheritance and development of festival customs comes from the cultural spirits and traditions behind the festivals’ customs. For this reason, Chinese people believe that their traditional festivals are rich in cultural significance, and consequently invest their emotions and beliefs in them.

In this study, Teacher C skilfully combined Chinese traditional culture with drama-based teaching methods and using two characters of the Mid-Autumn Festival - Change and Hou Yi. Teacher C and the children jointly created the story of Change and Hou Yi, who had experienced a good life together before parting ways. Teacher C also provided additional opportunities for children to feel the profound cultural heritage underlying the Mid-Autumn Festival, while guiding the children to engage in spontaneous role-play. In the course of such creation and play, it appears that the children’s understanding of the traditional customs and habits pertaining to the Mid-Autumn Festival were deepened. However, the study also seems to indicate that it may be difficult for them to have a sense of the national belonging immediately after the drama activities. Nonetheless, teachers should persist with weaving cultural content into the curriculum by means of drama-based pedagogy in the kindergarten whenever and wherever possible. The subtle influence of this approach and methodology may help to establish and maintain children’s cultural belonging in the future.