Introduction

‘… [A]cting engages not only your conscious control of body and voice but the unconscious portions of your human organism – your autonomic nervous system, above all, along with the sweat glands, emotions, tear ducts, and thousands of hidden processes that are under its control. These shape your heard intonations and resonances, your observed gestures and movements, and even your heartbeats and your respiration’ (Cohen, 2013, pp. 70–71).

This citation from Robert Cohen (2013) provides a detailed and rather physiological description of an actor’s embodied engagement when onstage. In this article we attempt to better understand Cohen’s (ibid.) description of bodily engagement in acting. We aim to present an interdisciplinary research perspective, which explores theatre improvisation using electrophysiological measurements in the context of teacher education. Therefore, instead of concentrating on professional theatre actors’ physiological processes (e.g., Greaves et al., 2022), our focus lies on applied improvisation and brain and bodily reactivity amongst nonprofessional individuals — in this case, student teachers. We will present a theoretical construct of applied and theatre improvisation, followed by a summary of empirical research that provides behavioural and psychophysiological evidence of the impact of applied improvisation on the aforementioned bodily processes.

Meisner and Longwell (2012, p. 15) defined acting as ‘living truthfully under imaginary circumstances’. Even earlier, Konstantin Stanislavski, renowned for his determination to develop natural and truthful acting, used improvisation (or etudes) during rehearsals to evoke actors’ creativity and stimulate their emotions so that the actors’ own inner selves might merge with the inner lives of the characters (Barton, 2018; Noice & Noice, 2018; Scholte, 2010; Stanislavski, 2011; Trenos, 2014). In this article, we also explore the relationship between improvised fiction and reality from a neuroscientific and psychophysiological perspective. In doing so, we ask the following: Does a fictitious improvisational exercise generate similar physiological responses compared to a real-life situation? This article summarises key findings from four studies (Seppänen et al., 2019, 2020; Seppänen, Novák, et al., 2021; Seppänen, Toivanen, et al., 2021), whilst a more detailed description of these topics can be found in Seppänen’s (2022) doctoral dissertation.

A theoretical model of theatre improvisation

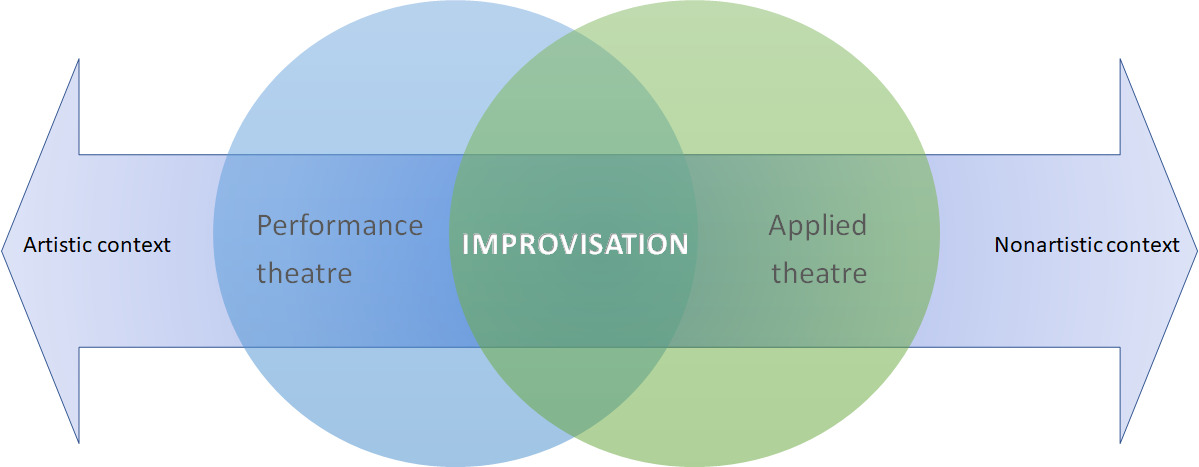

DeMarco (2012) theorised improvisation through a framework representing a continuum. The artistic end of the continuum refers to improvisation as an art form, whilst the nonartistic end refers to our existence in the world as we immediately respond and continually adapt to everyday environments (for example, when we meet people, answer a phone call, play football or teach a class). Seppänen (2022) used this continuum to study theatre improvisation at the intersection between performance and applied theatre (Figure 1).

In Figure 1, improvisation is represented in the context of performance theatre both as improvised plays on stage (a performance created on-the-spot without a script) and as a training method to develop actors’ resources, such as through imagination and stage presence. In addition to training the actor for improvised plays, improvisation is employed to develop a character role for traditional scripted plays, such as experimenting with a character’s reactions in off-scripted scenarios (Frost & Yarrow, 2015, pp. 62–63). Furthermore, improvisation can aid scriptwriting by generating material for a novel theatre play through improvised situations, characters and their relationships (Frost & Yarrow, 2015). For instance, devising places trust in improvisation to collaboratively create a performance (Heddon & Milling, 2015, p. 3).

The context of applied theatre brings together a broad range of dramatic activity carried out by a host of diverse bodies and groups (Bowell & Heap, 2010). The theatrical practices and principles are, in some cases, used in non-theatrical settings to achieve outcomes beyond the artistic experience itself, including for promoting empowerment, capacity-building or social transformation (A. Baldwin, 2009; Taylor, 2003). Although this article focuses on improvisation as a form of applied theatre, we must understand that the same kind of improvised practices are used in many other conventions of applied theatre (e.g., process drama, forum theatre and playback theatre) (Dudeck & McClure, 2018). All forms of drama and theatre are interpretations and expressions of human behaviour and meanings, which use time, space and presence to interact and imaginatively shape the creation of different kinds of meanings (Neelands & Goode, 2015, pp. 2–3).

Experiences and meaning-making from forms of theatre and drama require both intellectual and emotional engagement in dramatic actions. Neelands (2009) argues that the importance of drama in schools lies in the processes of social and artistic engagement and in experiencing drama rather than in its outcomes. According to Dunn, Bundy and Stinson (2015, 2020), to achieve this it is important that the facilitator understands that selecting the dramatic strategies (e.g., drama conventions) generates dramatic tension, which individuals experience individually with high levels of commitment, connection and diverse emotions. Emotions are critical to those who are engaged in works of drama. Emotions are also linked to learning — a large body of evidence has established that emotional events are remembered more clearly, accurately and for longer periods of time compared with neutral events (Tyng et al., 2017).

Given that emotional engagement is embedded in dramatic action, careful consideration must be given to the balance between emotional engagement and psychological safety (Dunn, 2016). To create a psychologically, socially and physically safe learning environment, a ‘drama contract’ should be established, wherein the ground rules (behavioural and procedural expectations during the dramatic work) for the group are discussed and agreed upon (P. Baldwin, 2008, pp. 46–47; P. Baldwin & Neelands, 2012, p. 102). Hunter (2008) identified four ways in which the phrase ‘safe space’ might be used in the context of applied theatre, improvisation and theatre work:

-

First, a space that is physically safe is one in which bodies are not exposed to harm or danger, as in a studio or theatre space that perhaps has no broken floor planks or exposed electrical wires.

-

Second, a metaphorically safe space is one in which participants are safe within a physical and temporal space, like a workshop, where they will not be discriminated against and where they are safe from prejudice and intolerance.

-

Third, the kind of safe space is one in which a person feels at home, where safety is bound to familiarity and the ‘space becomes safe as it becomes known’.

-

Finally, a safe space is one in which participants are safe to take risks, more specifically, creative risks.

A core component in generating psychological safety in drama and improvisation lies in the use of fiction. Process drama or each individual improvisational scene takes place in fictional time and place, where participants assume roles, allowing them to ‘walk in the shoes of others’. This mutually agreed upon fiction creates a cognitive and emotional distance, allowing experimentation with new attitudes and modes of behaviour and facilitating the confrontation of sensitive topics (Mendelson & Papacharissi, 2007). Furthermore, the drama contract should be continually monitored by the facilitator and readjusted in case fictional content generates stress or anxiety within the group.

Applied improvisation

In this article, we use applied improvisation as an umbrella term, referring to an approach of using theatre improvisation techniques in non-artistic contexts as a tool to pursue specific goals (Tint & Froerer, 2014). According to Frost and Yarrow (2015, p. 66), applied improvisation may serve as an experiential learning tool in different environments in which personal capabilities can be renegotiated. They recommend not focusing merely on the technical skills of improvisation (games and drills that can be taught and learnt), but also on understanding the ‘meta-skills’ at play, such as tolerating uncertainty, risk-taking, an ability to remain present and using signals and impulses within oneself and in the environment.

Fields requiring adaptability, creativity, reciprocity and a tolerance for uncertainty have benefited from applied improvisation. For example, research on creativity and divergent thinking has consistently identified the positive effects of improvisation interventions (Celume et al., 2019; DeBettignies & Goldstein, 2019; Felsman et al., 2020; Hainselin et al., 2018; Schwenke et al., 2020; West et al., 2017). Alongside individual creativity, co-creativity has been studied within contexts such as teaching (Drinko, 2018; Sawyer, 2003, 2004, 2011, 2012; Shem-Tov, 2015; West et al., 2017) and organisational creativity (Gerber, 2009; Hodge & Ratten, 2015; Ratten & Hodge, 2016; Vera & Crossan, 2004, 2005). Furthermore, fields such as medical education (Gao et al., 2018; Hoffmann-Longtin et al., 2018), marketing skills (Mourey, 2020), clinical social work and psychotherapy (Romanelli et al., 2017; Romanelli & Tishby, 2019) and humanitarian aid (Tint et al., 2015) have all benefited from improvisation interventions.

Applied improvisation in teacher education

The idea of applying improvisation to teacher education is not new. For instance, in 1967, Dorothy Heathcote, a pioneer of educational drama, argued that improvisation is not merely a subject area, but also a tool for science teachers and arts (Heathcote, 1967). Similarly, Özmen (2010; see also Aadland et al., 2017) justified incorporating theatre-acting theories into teacher education because certain areas of actor training might contribute to teacher education and to the development of teacher identity. For example, acting resembles teaching in that it requires capturing and holding the attention of an audience (or class), using one’s voice and body language effectively and following a script (or a lesson plan) to communicate predefined meanings.

The relationship between performing and teaching has also been studied. For instance, Whatman (1997) emphasised the similarity between role adoption in performing and teaching, and proposed re-examining teaching as an art, specifically as an improvisational art. In addition, Sawyer (2004) extended the metaphor of teaching as an improvised performance by including classroom discussions. Thus, a classroom discussion is understood as improvisational because the flow of the class is unpredictable, emerging from teacher and students simultaneously, resembling processes found in theatre improvisations (see also Barker, 2019). Furthermore, Maheux and Lajoie (2011) state that improvisation takes place in teaching whenever a teacher allows for students’ questions or explanations, solicits their reasoning or observations or asks them to explore and come up with their own procedures. The point of departure lies in recognising the inherent unpredictability, which bridges teaching with improvisation. Morales–Almazan (2021) used improvisation as a metaphor for active and creative teaching, which aligns with the emotional and cognitive states of students (see also Lehtonen et al., 2016). Since improvisation in the arts can be taught and mastered systematically, the same approach applies to developing and promoting active teaching. Along this line, Toivanen et al. (2011) suggest that improvisation training serves as one way of improving teacher education, since teachers must possess the ability to manage unrest, uncertainty and unpredictable situations. In the studies summarised here (Seppänen, 2022; Seppänen et al., 2019, 2020; Seppänen, Novák, et al., 2021; Seppänen, Toivanen, et al., 2021) improvisation as an actor training method (Johnstone, 1989, 1999; Spolin, 1999) was applied to the context of teacher education to promote student teachers’ interpersonal competence. In this context, interpersonal competence refers to the motivation, knowledge and skills associated with social interactions, in line with Spitzberg’s competence theory (1981).

In what follows, we focus on two research issues. First, we concentrate on the behavioural and psychophysiological findings of improvisation interventions conducted for student teachers in order to promote their interpersonal competence. Second, we focus on whether and how brain and bodily responses differ during real-life dyadic interactions and similar fictional, improvised interactions.

Implementation of the research methodology in the summarised studies

Seppänen et al. (2020) measured the impact of improvisation training using psychophysiological methods in the context of teacher education. Specifically, they examined whether an improvisation intervention decreased student teachers’ social stress and promoted interpersonal confidence, that is, the belief regarding one’s capability related to effective social interactions. Student teachers (n = 19) participated in a 7-week improvisation intervention, consisting of the fundamentals of theatre improvisation. All sessions began with a physical warm-up, following which the principles of improvisation were introduced using exercises such as 1) games related to tolerating failure; 2) listening exercises; 3) exercises on an ‘empty mind’, that is, resisting the temptation to plan one’s actions and being ready to react to any unpredictable actions from others; 4) exercises on accepting versus blocking; 5) status expression exercises; and, finally, 6) short, low-threshold improvisation techniques performed by two to four participants at a time in front of the entire group.

The intervention included a pre-course task which focused on describing previous experiences of social stress and expectations from the improvisation course. In addition, participants completed weekly tasks centred on observing everyday social interactions outside the class, such as finding examples of the topics addressed during the improvisation sessions. Participants also kept a learning diary in which they reflected upon the feelings they experienced and their insights throughout the course, submitting a summary of their learning diaries as their final course assignment (for more details regarding the improvisation intervention, see Seppänen et al., 2019). The intervention study included a control group (n = 20) of student teachers, whose improvisation course was arranged following the intervention study. One year later, a follow-up study was conducted to determine the long-term effects of the improvisation intervention.

The same sample of student teachers (n = 39) also participated in another study (Seppänen, Toivanen, et al., 2021) which explored how the perceived fictionality in improvisational scenes influenced brain and bodily responses by comparing psychophysiological reactivity during fictional and real-life contexts.

The psychophysiology of improvisation

When investigating improvisation, the research methodology has been characteristically qualitative and ethnographic in nature. Interviews provide information about individuals’ experiences, perceptions, desires and thinking patterns. Observations, whether on-site or through video recordings, reveal possible changes to behaviour following an intervention. Quantitative methods are utilised as well, although the weakness of questionnaires lies in the fact that they do not deeply reach the emotional arousal that a drama experience — such as that experienced during improvisation — stimulates (Costa et al., 2014).

Improvisation is a multisensory experience activating the visual, auditory, motor and social areas of the brain as we watch, listen and act during games, rehearsals or scenes. In addition, given that these exercises frequently evoke emotional involvement, the emotional brain circuitries activate as well (Costa et al., 2014). Since emotional experiences are as much physiological as experiential events, physiological measurements can provide information about those basic biological and unconscious processes associated with arousal and emotional valence (that is, biosignals) which cannot be accessed through self-reports. Continuous data from and the temporal precision provided through biosignals can supplement the information provided by self-reports since a retrospective self-report might misremember the details of the experience. Moreover, biosignals remain unaffected by the linguistic abilities of participants and are not confounded by social desirability (Mauss & Robinson, 2009; Ravaja et al., 2006).

Yet, little empirical research linking theatre improvisation with psychophysiological measurements exists. Theatre-based exercises such as the mirror game (a silent pair exercise where one leads the movement and the other follows, or both can lead or follow simultaneously) have been utilised in psychophysiological research (Noy et al., 2015). During a dyadic mirror game, both players exhibited increased cardiovascular arousal and an alignment of players’ heart rates emerged during spontaneously emerging states of togetherness (Noy et al., 2015). Along similar lines, Himberg et al. (2015) used magnetoencephalography in a study of interpersonal synchrony during a word-by-word exercise (joint storytelling by saying one word in turn) and found strong spontaneous adaptation of a speech rhythm between conversation partners. In addition, electroencephalography (EEG) has been used when studying the word-by-word exercise as a paradigm for investigating social interactions (Goregliad Fjaellingsdal, Schwenke, Ruigendijk, et al., 2020; Goregliad Fjaellingsdal, Schwenke, Scherbaum, et al., 2020).

The impact of applied improvisation on acute social stress and interpersonal confidence

Teaching is connected to being exposed daily in front of students, colleagues and, at times, parents. Being in front of others may generate social anxiety and stress — that is, the fear of being negatively evaluated by others relevant to the individual (Wiggert et al., 2015). The literature indicates an association between improvisation training and diminished social anxiety (Casteleyn, 2019b, 2019a; Felsman et al., 2018; Krueger et al., 2017; Phillips Sheesley et al., 2016). In line with previous research, Seppänen et al. (2020) explored whether a 7-week improvisation intervention decreased student teachers’ acute social stress and promoted interpersonal confidence.

The impact of the improvisation intervention was measured before and after the intervention using subjective self-reports and recording participants’ biosignals during a highly standardised Trier Social Stress Test (TSST) in a laboratory environment (Kirschbaum et al., 1993). TSST includes two tasks: an impromptu speech and a challenging mental arithmetic task performed in front of a jury (Allen et al., 2016). In addition, the preparatory phase (a short period for planning the speech) is considered an essential part of the test to examine the anticipatory anxiety of public speaking (Boehme et al., 2014; Gonzalez-Bono et al., 2002; Lorberbaum et al., 2004).

The biosignals analysed included participants’ heart rate, electrodermal activity, facial muscle activity, electrocortical activity (EEG alpha asymmetry) and the cortisol level. Electrodermal activity, or a change in skin conductance (e.g., sweating palms during a stressful situation), is an index of autonomic arousal under social stress (Cacioppo et al., 2007; Kelly et al., 2012; Levenson, 1992). The augmented activity of the zygomaticus major (the facial muscle generating a smile) associates with a positive emotional expression, and the increased activity of the corrugator supercilii (the ‘frowning’ muscle, pulling the eyebrows downwards and together) with a negative emotional expression. This minuscule muscle activity can be measured even if the person shows no outward facial expression or reports any conscious emotion (Cacioppo et al., 1986; Wiggert et al., 2015). EEG alpha asymmetry, a relative hemispheric difference in the frontal cortical activity, is a measure reflecting behavioural motivation to approach or withdraw (Davidson, 1993; Davidson et al., 2000). Finally, an increased cortisol level is a strong indicator of a neuroendocrine stress response to a social-evaluative threat (Blackhart et al., 2007; Düsing et al., 2016).

Seppänen et al. (2020) found that at the post-test measurement the improvisation intervention diminished pre-performance stress, or anticipatory anxiety, indexed by more relaxed facial muscles and an increased heart rate variability (HRV) compared with the pre-test measurement. HRV, the oscillation in the interval between consecutive heartbeats, yields information on the ability of the cardiovascular system to adjust to sudden physical and psychological challenges (Malik et al., 1996; Shaffer et al., 2014; Shaffer & Ginsberg, 2017). Moreover, self-rated stress during the maths task decreased among the low interpersonal confidence intervention subgroup. This heterogeneous treatment effect supported their previous finding (Seppänen et al., 2019) that the low interpersonal confidence intervention subgroup benefitted the most from improvisation training. Interestingly, the control group also exhibited decreases in cardiovascular stress during some of the test conditions. The lower stress responses in the control group suggest that the repetition of a challenging task, such as a public speech, can generate habituation.

In the follow-up study conducted one year later, they found that self-rated performance confidence — a sub-feature of interpersonal confidence[1] — persisted at a higher level relative to the control group (Seppänen, Novák, et al., 2021). Again, improvisation training fostered performance confidence amongst those who scored lower on the pre-test, indicating that less confident student teachers gained the most long-term benefit from the improvisation intervention.

These findings agree with DeBettignies and Goldstein’s (2019) study on the impact of improvisation training and Wright’s (2006) study of drama on school children’s self-concept — that is, how students perceive their status and abilities. Both studies found a positive training effect, but only amongst children who began with relatively lower levels of self-concept. While self-concept represents a more general construct than performance confidence, these results suggest that the gains from interventions may be related to the initial level of the targeted psychological construct.

The extensive desensitisation of a fear of failure during improvisation training might represent the core component of reducing social stress. From a psychological perspective, improvisation might be regarded as an emotion regulation strategy of cognitive reappraisal in terms of the meaning of mistakes (Brooks, 2014; Gross, 1999, 2015; Kalisch et al., 2005; McRae, 2016; Seppänen et al., 2019). Cognitive reappraisal involves changing the way we think about a situation to change how we feel about it (McRae, 2016, p. 119). Redefining mistakes as events, whereby merely something other than what was anticipated happened, and changing the emotional connotation of mistakes from negative to positive may reduce social stress since no pressure to succeed exists. This suggestion is supported by the study of Seppänen, Novák et al. (2021) amongst a larger sample (n = 161), whereby a tolerance for failure, another subfeature of interpersonal confidence, increased following improvisation training (5 to 10 weeks) relative to controls. As the fear of failure diminishes, it is possible to allocate attention-related resources outward, instead of monitoring one’s own feelings of distress (Drinko, 2013a; Rapee & Heimberg, 1997). Assuming that less confident student teachers were more stressed during social encounters, they would likely benefit more from learning to tolerate mistakes and disengage from rumination. This might channel their cognitive resources to perceive the subtleties of the social situation (e.g., voice prosody and nonverbal expressions), leading to more situation-sensitive social interactions, which in turn might promote interpersonal confidence.

Brain and bodily responses during real-life and fictional stimuli

Fiction lies at the heart of theatre art and improvisation. Although improvisational scenes frequently represent reality and everyday social interactions, improvisers acknowledge the fictional quality of their characters’ roles and the fictional context of a scene. Seppänen, Toivanen et al. (2021) explored how this perceived fictionality in improvisational scenes influenced brain and bodily responses amongst student teachers by comparing their psychophysiological reactivity in both fictional and real-life contexts.

The real-life context was represented by an interview, whilst the fictional context through improvisation games. Both contexts involved three types of subtle social rejections as stimuli: devaluing (e.g., ‘Yes, I can see your point, but isn’t it a bit outdated?'); interrupting a conversation partner; and nonverbal rejection (showing signs of boredom, avoiding eye contact and the like while the partner spoke). In the real-life context, participants (n = 39) were unaware that the interviewer was an actor trained to include the aforementioned subtle social rejections during the 10-minute interview. Following the interview, a researcher conducted a brief improvisation game training session, which included the same subtle rejections as those experienced during the interview. Participants were told beforehand which rejection type would be employed during the improvisation game, so that they were entirely aware of the fictionality of the situation. The measures analysed included participants’ experienced stress, heart rate, electrodermal activity, facial muscle activity and electrocortical activity (EEG alpha asymmetry).

The main finding identified an absence of any systematic attenuation of brain and bodily reactivity to the fictional improvisation game training versus the real-life interview (Seppänen, Toivanen, et al., 2021). Regardless of cognitive awareness of fictionality, bodily responses during improvisation remained relatively similar and correlated positively with those that occurred during the real-life context. EEG alpha asymmetry values indicated that all social rejections, whether during fictional improvisation games or a real-life interview, elicited withdrawal-related cortical activity, whilst elevated levels of skin conductance indicated an increased physiological arousal during social rejections. When comparing responses across all rejection types, EEG alpha asymmetry and facial muscle activity did not differentiate between real-life and improvised rejections. Furthermore, both real-life and fictional devaluations evoked a heart rate deceleration effect, a transient deceleration of the heart rate associated with feedback processing, such as social rejection (De Pascalis et al., 1995; Eisenberger et al., 2003; Gunther Moor et al., 2010; van der Veen et al., 2014).

These findings suggest that at the bodily level the rejection-related physiological responses were rather similar in simple fictional improvisation games to those in real-life situations. Consequently, the findings support the view that fictional representations of reality can generate genuine emotional experiences. Interestingly, this study also found a stronger physiological reactivity during fictional relative to real-life interruptions, a finding that contradicts previous research which reported either an emotional or physiological downplaying associated with fictional stimuli (e.g., Abraham et al., 2008; Mocaiber et al., 2010; Sperduti et al., 2016) or similar emotional and physiological responses in real-life and fictional contexts (Goldstein, 2009; Gorini et al., 2010; Kisker et al., 2019; Zadro et al., 2004).

Personal relevance might explain the absence of a systematic attenuation of an arousal or valence related to the fictional stimuli. Personal relevance refers to processes such as personal memory retrieval and the processing of personally salient information (Abraham et al., 2008; Abraham & von Cramon, 2009; Sperduti et al., 2016). The tasks performed in this study required personal engagement using the participants’ imagination and resulted in spontaneous associations and input during the tasks. In other words, participants were active agents rather than passive observers of the stimuli. Perhaps the rejection of these personal associations counteracted against the cognitive processes of downplaying fiction and generated a relatively comparable physiological reactivity to real-life rejections (Seppänen, Toivanen, et al., 2021). The relevance of this finding extends to applied theatre in general, which relies on holistic actions and personal engagement in fictional contexts (H. Cahill, 2010; Henry, 2000).

Discussion

In this article, we aimed to present an interdisciplinary research perspective to explore theatre improvisation using electrophysiological measurements in the context of teacher education. Keith Sawyer (2011) argues that great teaching requires both structuring elements and improvisational brilliance. Whilst planning lessons is a crucial component of an instructor’s professional skills, a readiness to also abandon a plan and intuitively shift the course of action according to situational challenges — in other words, a responsiveness — plays an equally important role. According to Coppens (2002), an instructor should be continually ready to integrate unexpected contributions from students and the environment. This situational sensitivity and responsiveness as well as intuitive thinking can be practised through applied improvisation (Aadland et al., 2017). As such, Drinko (2013b) and Lobman (2006) argue that improvisation training enhances listening skills and situation-focused sensitivity, leading to a heightened perception of subtle verbal and nonverbal cues from learners and, ultimately, to better ensemble collaboration. The findings presented in this article agree with previous research, suggesting that including applied improvisation in teacher education curricula can enhance student teachers’ interpersonal competence as well as their skills related to sensitive and responsive teaching.

Since the studies summarised here demonstrate that on a physiological level the rejection-related psychophysiological responses were rather similar when comparing simple fictional improvisation games and real-life situations, this finding highlights the importance of psychological safety in applied improvisation and theatre, especially when dealing with challenging topics. Although the study of Seppänen, Toivanen et al. (2021) compared real-life and fictional contexts, the results do not imply that fictional experiences in an educational context should equate with real-life experiences. Equivalent experiences might even become harmful when the topic is challenging, dealing with issues such as bullying at school or work or other forms of violence. Given that fictional rejections can elicit emotional arousal comparable to real-life situations, a teacher or facilitator should carefully monitor the psychological wellbeing of participants when simulating challenging social encounters.

The interdisciplinary approach of the summarised research in this article provides a unique and more profound understanding of what ‘living truthfully under imaginary circumstances’ — the core concept of theatre and drama — means on a physiological level. The results demonstrate that considering psychophysiological responses, genuine emotions and realistic experiences can be generated in a fictional context. However, this finding may not represent paradigm-shifting news for professionals in drama education and theatre, individuals who frequently witness that engaging in fictional worlds can elicit emotional reactions both in the audience and amongst actors and/or participants. Nevertheless, Seppänen et al. (2019, 2020; 2021) have empirically tested this generally known phenomenon using both subjective and objective methods and supplemented existing knowledge with a new layer of biological findings. These results can be used to justify the use of fiction in various teaching and educational contexts, in practices which rely on holistic actions and personal engagement in fictional contexts, such as applied theatre, improvisation and drama in general (H. Cahill, 2010; Henry, 2000). This type of evidence is necessary when justifying the use of theatre-based methods and aiming for a change in, for instance, educational policies.

These findings also support the idea that applied theatre forms, such as process drama, which emphasise deeper contextual explorations of life and human relations, should be a part of all areas of a curriculum. The pedagogy of process drama connects classroom learning to the world beyond, establishing relevance and authenticity in learning, and asks complex questions about the world which includes but is not limited to school (Neelands, 2009).

Furthermore, the research presented here provides a pioneering model for integrating theatrical improvisation with neuroscientific measurements, which will also allow for cross-disciplinary work in future. Previous research has explored the psychological and physiological effects of real versus fictional stimuli using photographs and video clips (Goldstein, 2009; Mendelson & Papacharissi, 2007; Mocaiber et al., 2010; Sperduti et al., 2016). Seppänen, Toivanen, et al. (2021) extended this research further by using naturally unfolding, improvised face-to-face interactions as experimental stimuli. Whilst the controllability of the stimuli was compromised — due to the unpredictability of the improvisations — this attempt to extend the quality of stimuli to a more naturalistic, experiential nature seems justifiable given the ecological validity of the stimuli appears to make a significant difference. That is, complex and lifelike stimuli seem to activate the brain more and differently than discrete and static stimuli (Jääskeläinen et al., 2021; Risko et al., 2016).

Future research might investigate the relationship between experiential learning and memory formation, that is, the neural modulation and consolidation of memory traces (Hari, 2015; Hofer & Bonhoeffer, 2010). Experiential learning in improvisation and applied theatre possibly creates and activates memory traces connecting several neural networks (motor, visual, auditive, emotional and social) as we watch, listen and act together during the experiential learning process. This multimodal activation might strengthen memory traces as well as memory retrieval. In particular, an experience that contains self-relevant emotional information is retained in memory over time (L. Cahill & McGaugh, 1995; Dolcos et al., 2005; McGaugh, 2013; Tyng et al., 2017). This study raises the question of whether multimodal theatre-based practices can evoke stronger learning experiences (Costa et al., 2014; Hainselin et al., 2017) resulting in more enduring memory traces relative to learning, which includes fewer modalities such as visual (reading text) or audiovisual (listening to a lecture) modalities.

To conclude, we believe that the results of the studies presented here extend our understanding of the impact of improvisation training and the use of fiction for educational purposes, demonstrating that even a relatively brief improvisation intervention can enhance interpersonal confidence, particularly amongst those who most need it. In addition, improvisation training can mitigate acute social stress as measured by psychophysiological reactivity, and generate long-term improvements in performance confidence. This is important because a large number of actions in individuals’ everyday and working lives occur during social interactions — either face-to-face or online. We have noticed the meaning and importance of these interactions during lockdown periods within the last several years during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Although this research was conducted within the framework of teacher training, it strengthens the theoretical and empirical foundation for using applied theatre, improvisation and drama as tools to reflect human interactions and encounters in various fields from school teaching to continuing adult education. The results provide a rationale and novel empirical support for the application of improvisation as a tool to deal with interpersonal themes and promote social interaction competencies. Thus, these studies provide drama and theatre educators and directors with strong evidence to justify their work.

Funding details

The funding agencies were not involved in any part of this study.

Disclosure statement

The authors report that there are no competing interests to declare.

Acknowledgements

We extend our thanks to Vanessa Fuller (Language Services, University of Helsinki) for the English-language proofreading of this manuscript.

A confirmatory factor analysis identified six factors — performance confidence, flexibility, listening skills, tolerance for failure, collaboration motivation and presence — contributing to interpersonal confidence (Seppänen, Novák, et al., 2021).