Prologue

A burst of energetic laughter and raised voices bubbles from the group of students casually slouching outside Theatre Sixteen. “Our home away from home” says one student putting her arm around her friend. Their relaxed bodies stretch into and fill the space as they wait for their next class. Passionate voices echo down the corridor of painted concrete brick. Christina, their course coordinator, passing by casts an anxious eye towards the closed office doors of other staff members and the imagined tut-tutting at these loud, excitable students and their noise. She opens her office door, plastered with years of class photographs of past generations of Drama teachers - each one a reminder of those who have passed through this space.

Introduction

As veteran educators and researchers in initial drama teacher education, we have dedicated our careers to preparing and supporting the next generation of drama teachers. Alongside our students, we have celebrated their academic successes, professional milestones, creative achievements, and personal growth. We have also witnessed the mounting pressures they face - the rising anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic (Paris et al., 2023), the financial strain of completing teaching degrees (Fokkens-Bruinsma et al., 2023; Logan & Burns, 2023), and the scarcity of quality mentor teachers due to the ongoing national teacher shortage (DET, 2022; Eacott, 2023).

In this article, we draw upon these experiences, together with a series of narrative vignettes to amplify the voices of 22 Australian pre-service drama teachers. Specifically, we explore how beginning drama teachers’ motivations for entering the profession, memories of their own school drama experiences, and concerns about teaching inform their developing professional identity. Their insights provide a contemporary picture of what it means to step into the profession, while also supporting those working in drama teacher education to shape curricula that better prepare teachers for the realities ahead.

The notion of professional identity is central to understanding how beginning teachers navigate these transitions. Recent scholarship offers valuable perspectives on this theme within drama education. McConville and Ludecke (2021) use research-based theatre to illuminate how drama teachers construct and perform their professional selves, revealing the tensions and creative possibilities inherent in this process. Wales (2018) highlights how identity shapes practice and positioning, emphasising the influence of context and power in defining the drama teacher’s role. Complementing these Australian contributions, Kempe (2012) conceptualises drama teacher identity through the interplay of self, role, and character, showing how educators negotiate personal authenticity alongside professional expectations and performative dimensions of teaching. Together, these studies underscore why professional identity is a critical lens for examining the lived experiences of drama teachers.

Our positionality as researchers requires acknowledgement. Both authors work in initial drama teacher education, and one of us has a teaching relationship with the participating students. We recognise that this dual role as educator and researcher may have shaped the interview dynamic and thus, we emphasised confidentiality, voluntary participation, and the separation between coursework and research involvement. At the same time, our shared experience as drama educators provided insider knowledge that enriched the research, enabling us to interpret students’ accounts with greater nuance.

Our research takes place in a climate of uncertainty within teacher education, shaped by hypercritical neoliberal performance pressures (Gupta, 2021; Lambert & Gray, 2025) and the contraction of the arts (National Advocates for Arts Education, 2024). Yet, amid these challenges, these pre-service drama teachers radiate optimism. Their experiences, captured in this study, offer a portrait of this moment in time - a glimpse into both the struggles and the enduring passion that define the next generation of drama teachers. In doing so, this article contributes to wider conversations on teacher identity by showing how personal motivations, remembered experiences, and professional concerns converge in the making of drama educators.

Literature

Initial teacher education serves a dual purpose, providing the vocational training necessary for teaching while also fostering a broader educational philosophy. It equips future educators with foundational skills and experiences, helping them navigate the apprenticeship of teaching as a profession (Daza et al., 2021). At its core, teacher education weaves together key domains of knowledge - Content Knowledge, Pedagogical Content Knowledge, and Curriculum Knowledge (Shulman, 1987), while also inducting educators into communities of practice (Dille & Røkenes, 2021; Wenger, 1998). In this section, we examine key literature that together frames how professional identity is cultivated in drama teacher education. Scholarship on initial teacher education provides the institutional and pedagogical context; research on communities of practice highlights the relational processes through which identity is negotiated; studies on effective drama teaching articulate the professional attributes and values that shape identity formation; and finally, literature on drama and transformation situates this development within the broader aesthetic and affective dimensions of the art form itself.

Communities of Practice

Communities of practice are central to how graduate educators establish their professional identities (Smeplass, 2025). Communities of practice emerge when groups engage in shared practices, build common repertoires of tools and language, and develop mutual accountability. For beginning teachers, this often takes the form of mentoring, collaboration with colleagues and participation in professional associations (Spyropoulou & Kameas, 2024). Within Arts education, communities of practice are particularly significant because of the art forms’ inherently collaborative nature - ensemble work, rehearsal processes, co-devised performances, and classroom practices all mirror the collective, participatory dynamics of a community of practice (Goble et al., 2021; Goopy, 2022). Engagement in these communities enables pre-service drama teachers to move beyond individual skill acquisition towards a sense of belonging within the profession (Aldossary et al., 2025; Gray et al., 2025; Neelands, 2009).

For us, working in drama teacher education, the ultimate goal is to graduate teachers who are not only well-prepared for the classroom but also positioned to sustain fulfilling careers within these professional communities (Gray et al., 2017; Martyn, 2022). Understanding what makes an effective drama teacher, therefore, requires attention not only to technical competence but also to the communal and relational contexts in which practice is embedded.

Hallmarks of Effective Drama Teaching

Research on effective drama teaching highlights the qualities and practices that shape teachers’ evolving professional identities. Wright and Gerber (2004, p. 57) explored the multifaceted nature of drama teaching, revealing six essential qualities of effective drama teachers:

-

Highly engaged in their teaching, fully attuned to their students, and consistently energised by their subject matter.

-

Encouraged students to take creative risks and provided an environment where experimentation was not only accepted but celebrated.

-

Empowered learners by adding value to their personal and artistic growth, ensuring that drama education was a transformative experience.

-

Actively shared their skills, built professional networks, and contributed to the broader drama education community.

-

Engaged in ongoing reflection, striving to refine their teaching practice.

-

Acted as ambassadors for drama and the arts, advocating for its significance within the curriculum and beyond.

Gray and Lambert (2019, p. 13) later expanded this framework, identifying four additional competencies that distinguish effective drama teachers:

-

Actively supported students’ social and emotional development, helping them build resilience and key life values.

-

Prioritised the cultivation of strong, authentic relationships based on trust and mutual respect.

-

Facilitated extracurricular drama activities, providing students with opportunities to connect, collaborate, and thrive in creative spaces beyond the classroom.

-

Above all, they were passionate advocates for the transformational power of drama education, understanding its potential to shape students’ confidence, self-expression, and ability to engage with the world.

These competencies are reflected in McLauchlan’s (2011) research, where Year 9 and 12 students in Ontario were interviewed to share their perspectives on what makes an effective high school drama teacher. The students emphasised the importance of a balance between subject expertise, pedagogical skill, and interpersonal qualities. They described the most impactful drama teachers as those who not only had a passion for teaching drama but also demonstrated a deep interest in teenagers. According to the students, effective teachers built trust, listened with acceptance, and approached their students with open-mindedness. Students’ valued teachers who were both knowledgeable and willing to learn alongside them. They respected educators who displayed vulnerability, and who did not pretend to have all the answers but instead embraced the shared journey of discovery. Effective drama teachers fostered a strong classroom community by ensuring students worked with all peers, not just self-selected friends. They also used ongoing assessment as a tool for teaching, learning, and motivation, reinforcing drama as a collaborative and evolving practice. Although somewhat dated, the study remains significant because it uniquely centres student perspectives, insights that continue to resonate with more recent understandings of effective drama pedagogy (Gray & Lambert, 2019; Kemp, 2024; Sinclair, 2015).

Learning Drama, Learning to Teach Drama

Learning to teach drama is an embodied process through which pre-service teachers construct their professional identities. A long-held perspective on drama teacher education emphasises that the way we learn drama mirrors the way we learn to teach drama (Anderson, 2003; Briones et al., 2022; O’Toole, 2011). Pascoe (2022) affirms that becoming an effective drama teacher requires mastering two interconnected perspectives: understanding how drama is learned and understanding how it should be taught to ensure students can fully engage with it.

Drama education is inherently experiential, learned through doing, observing, and participating in an ensemble (Coleman & Thomson, 2021; Heathcote & Bolton, 1995; Neelands, 2009). Future drama teachers develop their skills by engaging in theatre, modeling expert practitioners, and immersing themselves in a shared professional community - a ‘guild’ of drama educators (Pascoe, 2022). Teaching drama extends beyond technical instruction; it requires recognising drama as an art form with deep cultural and historical roots. Drama is hands-on, embodied, and deeply personal, engaging the body, mind, and spirit (Cahill, 2019; Gray et al., 2025; Kemp, 2024). Learning drama means understanding it as an aesthetic and social experience, one that shapes and reflects human stories (Anderson & Jefferson, 2019; Sinclair, 2015). Further, becoming an effective drama teacher is not just about mastering content but about embracing multiple roles. Drama teachers serve as educators, curriculum leaders, directors, mentors, and resource managers. Learning to teach drama is a practical and embodied experience, requiring pre-service teachers to experiment with strategies, concepts, and approaches that refine their decision-making in the classroom.

The research on drama teacher education reveals the most effective drama teachers are not only skilled practitioners but also mentors who inspire through their practice (Gray et al., 2018). To be ‘inspiring’ is not simply a matter of charisma but involves modelling professional integrity, fostering motivation, and creating conditions for risk-taking and growth (McLauchlan, 2011; Wright & Gerber, 2004). Inspiration emerges through a balance of expertise, openness, structure, creativity, and relational trust. When enacted in this way, drama teachers are positioned to foster rich and transformative learning that can shape both artistic engagement and students’ sense of self.

Drama and Transformation

Drama education invites transformation not only for students but also for those who teach it. The embodied, relational, and imaginative nature of drama means that teachers, too, participate in processes of learning, reflection, and change. Literature on drama and transformation therefore offers a way to understand how aesthetic and emotional experiences influence teachers’ developing sense of self and purpose.

There are many claims for drama as a transformational experience (Chinyowa, 2009; Freebody et al., 2018; Taylor, 2003), and drama teaching being transformative (Nicholson, 2005; Thompson, 2006). The Cambridge Dictionary (2024) states, to transform is to “change the appearance or character of something or someone, especially so that that thing or person is improved.” In educational literature, transformation is most commonly conceptualised through Mezirow’s (1991, 1998) theory of transformative learning, which describes a process of deep structural change in the ways individuals think, feel, and act. It occurs when learners critically reflect on their assumptions, encounter disorienting dilemmas, and reconstruct their perspectives to achieve more inclusive and self-aware understandings. Transformative processes are not confined to drama or the arts; they are also claimed in disciplines such as health, leadership, and higher education, where learning involves personal change and the re-examination of professional values (Illeris, 2014). In the context of drama education, transformation can occur through participation, reflection, and relational encounters that challenge and expand the self, whether as learner, performer, or teacher.

Gadja (2016) conceptualises pedagogical transformative drama as a form of therapeutic engagement aimed at identity reconstruction and psychological well-being. Drawing on Fischer-Lichte (2004), she emphasises transformation through aesthetic experience and liminality, where the boundary between art and life becomes blurred, enabling deep psychological and emotional shifts. Gadja aligns her framework with Mezirow’s (1998) and Freire’s (1996) theories of transformative learning, situating drama within broader processes of cultural and social change. Transformation, in this context, involves self-directed learning, critical reflection, and an openness to others’ perspectives which is key to fostering creative and responsive educational environments. Gadja (2016) also links this to ancient drama structures and Grotowski’s emphasis on action as a form of personal and social revolution.

Maxine Greene (1995, 2010), building on Dewey’s philosophy, provides a robust theoretical foundation for drama as aesthetic education. As articulated by Gulla and colleagues (2022), Greene viewed aesthetic experiences as catalysts for personal and collective transformation. Drama fosters imaginative awareness and provides spaces in which learners can envision alternative ways of being.

Roberts and Yoon (2022) argue that personality traits can evolve through sustained experiences, while Wirag (2024) explores how drama influences motivation, empathy, creativity, and anxiety, identifying shifts in personality states resulting from role-play, improvisation, and group dynamics. The research suggests that drama can foster long-term personality development by engaging learners in recursive, emotionally rich experiences (Anderson & Jefferson, 2019; Bryce et al., 2004; Gibson & Ewing, 2020). Though this field is emerging, it offers promising insights into drama’s transformative potential in educational contexts (Goble et al., 2021; Sincuba, 2024).

Taken together, this body of work highlights drama as a collaborative, relational, and transformational field of practice in which professional identity is forged through both training and lived experience. Building on these insights, our study extends this scholarship by examining how pre-service drama teachers themselves articulate this process of becoming. Specifically, we explore how their motivations, memories, and concerns intersect to shape their emerging professional identities. These three dimensions guided the interview questions and frame our overarching research question: How do beginning drama teachers’ motivations for entering the profession, memories of their own school drama experiences, and concerns about teaching inform their developing professional identity?

Methods

Following institutional ethics approval (2024-05524), we conducted semi-structured focus group interviews with 22 pre-service drama teachers, comprising 13 who identified as female, seven as male, and two as non-binary. The focus-groups, each involving four to eight participants, were conducted in November, 2024. All participants were completing a Bachelor of Education or Master of Teaching degree with a drama major. The average age of pre-service teachers was M=21 and came from a range of cultural backgrounds.

Guiding questions for the focus group interviews included: (1) Why do you want to be a Drama teacher? (2) What do you remember about your high school Drama teacher? (3) As a beginning Drama teacher, what do you think you need to learn? and (4) Are there any aspects of teaching Drama that you are worried about? These questions were deliberately aligned with the study’s focus on motivations, memories, and concerns, enabling us to explore how these dimensions inform professional identity formation. Audio recordings of the interviews were manually transcribed verbatim by the researchers, and pseudonyms were assigned to protect participant identities. The research team conducted a thematic analysis of the transcripts, following the processes outlined by Braun and Clarke (2022). This involved three phases: generating codes, searching for themes, and reviewing themes. Authentic phrases and reflective nouns were used where patterns emerged. Focused thematic coding was then undertaken in the second and final cycles, with code categories examined closely for patterns of salience, inconsistency, relativity, and affect.

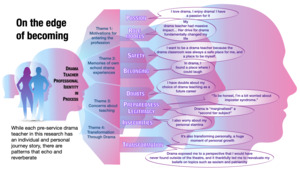

The findings are presented thematically. This approach highlights recurring patterns and shared experiences across participants, while preserving the distinctive language and tone of their reflections. The four key themes that emerged illustrate the complex interplay between motivation, memory, and concern in the formation of professional identity.

Findings

Each pre-service drama teacher in this research has an individual and personal journey story but there are patterns that echo and reverberate. The following themes focus on passion and role models; safety and belonging; doubts and insecurities; and transformation through drama. Each theme will now be presented in turn.

Theme 1: Passion and Role Models

It is evident that all participants have a passion for drama and discuss the influence of their drama teachers and own experiences in shaping their decision to be a drama teacher. Bea explained:

I love drama. I enjoy drama! I have a passion for it. I feel connection with other people, making meaning, expressing emotion and I would love to make the space for that to happen teaching that to students. I am not good at lots of practical things, I can’t drive yet; but when I am in a room with 30 other people, all excited, pointed in the same direction, bouncing ideas off each other, it’s the coolest experience ever. I love drama and I think I have the power to make others love it too.

My drama teacher had massive impact, making my passion for drama flourish through a bubbly personality that made me excited to be in class. She was weird and wonderful and fun in the best possible way. I remember fondly the influence she had. She was so passionate. Her drive for drama fundamentally changed my life, going from a ‘radiator kid’ to a fully-fledged drama nerd because of her. She was like a mother to me. My school drama experience was wonderful and important. It was the first time I felt good enough and liked the me I wanted to be that was finally starting to peek through.

More than that though, she revitalised our theatre program at school and made it something people cared about. School for the most part was something you just got through, but drama gave me somewhere to belong

Bea’s story is a window into the importance of being passionate about something. In choosing a career path, pre-service drama teachers like her respond to an inner drive. Zac saw in his drama teacher’s passion “a love of kids, connection and making a difference… being cheeky and playful and colourful… energy, zing, life uplifting … and I want to be like that.”

These comments suggest that for Bea and Zac effective role models were significant in helping them make a choice to become a drama teacher. Here, passion is not only a personal feeling but also a professional resource and something participants see as transferable to their future students and central to their teacher identity. The presence (or absence) of role models provides a template against which they position themselves, shaping their sense of what kind of teacher they aspire to become.

But it is important to note that pre-service drama teachers are also reflective and self-aware. Not all drama teachers provided effective role models on which to build a future career. Angela, for example, noted: “My drama teacher often went into anecdotal rants, occasionally lost his temper, and had clear favourites”, while Maddy called her teacher “hell spawn, squashing my love for drama and [being] overly critical.” These contrasting accounts suggest that role models function as both inspiration and caution, with negative experiences prompting participants to consciously reject certain practices and values. Memories of drama teachers, both positive and negative, become building blocks in the construction of professional identity.

Theme 2: Safety and Belonging

Most of the participants recognised and celebrated how “Drama provides students with an opportunity for transformation, allowing them to break away from the monotony of school routines” (Natalie). Ansel explained:

I want to be a drama teacher because the drama classroom was always a safe place for me, and a place to be myself. I was in the ‘smart’ group at school but never really as smart as my friends, but somehow drama allowed me a space to be myself. I used to be anxious, shy. I think I still am, but I’ve been encouraged to worry about it less. One day I realised that I had never laughed in school. Never. It was all serious business. In drama, I found a place where I could laugh.

I have positive memories of my drama teacher. She has a heart of gold, a laugh like no other, and a true passion and talent for teaching theatre. She tailored her pedagogy to unlock success in every one of her students. I am lucky enough to have maintained a relationship with her post-graduation, and she is one of my mentors throughout university and hopefully beyond. She helped me grow and start loving school again.

I was a kid from a troubled background. Everything changed for me. I could become free, someone else. She saw me, the first teacher who ever saw me. I want to fuel the flames so people like me can feel safe.

My Original Solo Production in Year 12 was the scariest thing I have ever done. Who knows how I did it. For me, it was about trust. Trusting myself and trusting others.

These words from Ansel suggest that within drama, their class was not only encouraged but actively urged to explore and express their individuality. Ansel also echoes the first theme of the significance of drama teachers as role models. Rachael reinforced this based on her experience, explaining that in her drama class they were encouraged to “delve into self-discovery both on personal and social levels, with the drama teacher facilitating and guiding this journey.” Meanwhile Stella, like other participants, described drama as “a safe place for me.”

These perceptions reveal that safety and belonging are not peripheral benefits of drama education, but central to how participants understand themselves as learners, with this potentially influencing their work as future teachers. For many, the drama classroom was the first space where they felt seen, valued, or free to express themselves, and these experiences shaped their motivation to enter the profession. Safety here is not only about emotional comfort but about the trust required to take creative risks, while belonging is framed as a foundation for confidence and identity development.

As pre-service teachers recall these formative experiences, they begin to conceptualise their own professional role as creating similar spaces for their students. In this sense, their memories of safety and belonging function as a pedagogical compass, guiding them toward practices that prioritise inclusivity, trust, and relational care as essential components of drama teaching.

Theme 3: Doubts and Insecurities

In spite of these mostly positive statements, there are also undercurrents in the conversations with pre-service drama teachers revealing a range of issues, including confidence and burnout. Beau’s comments capture these doubts and insecurities best:

I have doubts about my choice of drama teaching as a future career. Teaching seems like a wonderful second option. I didn’t want it straight away, which is why I’m here having done an undergraduate course in theatre rather than going straight from high school. Now that I’ve lived a bit of life it feels like a natural progression for me to do the thing I love and hopefully engage students with my passion for the subject. But I could easily slip away from teaching to running a bar, something I am already doing to support myself through university studies.

I am doing okay in this course and think I will make it into the classroom as a teacher. For a few years at least. But I keep reading on my news feed about teachers going on strike. What if I am going into teaching as a career, and it doesn’t pay off? Like, I worry about engaging students who have absolutely zero interest in drama. These students matter too! Will I fail them? Kids today are different from when I was in school. They’re on their screens looking at stuff that burns their soul. Where’s their drive and passion? I see them on the bus in their school uniforms and they’re loud and angry.

I also worry about my personal stamina. I find myself getting caught up in the excitement of the drama classroom, and my constant energy results in me losing my voice or feeling fatigued. I need to learn how to maintain being a positive and enthusiastic role-model in the classroom without overexerting myself.

As he heads off, he notes, “I think I need to learn that not everyone connects to drama the same way I do. And that way I won’t be disappointed.”

Other participants also highlight their doubts and questions, including reflections on the gaps in their current course and their capacity to respond to the needs of students. For example, Mica noted, “I need to learn how to build students up in drama over a long period of time” while Rona said, “I think my theory knowledge needs a bit of work.” Even Bea added, “To be honest, I’m a bit worried about imposter syndrome.” There are also doubts about finding a place in schools (Kristen), worries that drama is “marginalised” (Anita) and a “second tier subject” (Peta). Cilla added, "I’m also concerned about the parents’ expectations. It appears these pre-service drama teachers have a sense of having to “prove themselves” (Sarah) and their career choices to a sometimes-hostile world - reminding us that not everything in drama teacher education is without risk.

These insecurities also reveal how professional identity is negotiated in tension with systemic, personal, and pedagogical concerns. On the one hand, participants express doubts about their stamina, skills, and confidence; while on the other, they recognise structural challenges such as the marginalisation of drama and external scrutiny from parents or society. Such uncertainties signal not weakness, but the reflective questioning that often accompanies entry into professional life. Indeed, doubts and insecurities are identity-shaping. They highlight the fragility of belonging within a contested subject area but also point to the resilience and adaptability required of beginning teachers. By articulating their fears, participants begin to define what they must learn, guard against, or reimagine as they move towards becoming drama educators.

Theme 4: Transformation Through Drama

The final theme to emerge via the analysis process was recognition by many of the potentially transformational qualities of drama. However not everyone was convinced. For example, Amy posed the question, “How does drama work for some kids and not for others? I mean, you all love drama. [But] I’m doing it because I want to be an English teacher and I have to take a minor.” Bea was quick to respond but Harry was quicker:

Drama is transforming. It was for me. In Year 11, when we collaboratively devised a show about toxic masculinity and misogyny in private boys’ schools. It was an extremely vulnerable process that required a high level of honesty and introspection. It exposed me to a perspective that I would have never found outside of the theatre, and it thankfully led me to reevaluate my beliefs on topics such as sexism and patriarchy.

Bea chimed in:

So, it’s transforming about the world. It’s also transforming personally. One that comes to mind is my first intro to performance as an eight-year-old girl. I was super shy and softly spoken but a teacher saw my potential and cast me in the school production of Matilda as Mr Wormwood. It was a huge moment of personal growth for me as I absolutely lit up on stage and it boosted my confidence big time and really kickstarted my love for drama.

Jasmine quietly added:

Growing up, I always thought acting was the go-to option for me, but turns out I really enjoy guiding and organising. I love the idea of directing, yet my experience in a stage management roll was eye opening. From year 11-12, I was stage manager for our whole school production, and it really opened my eyes. It was like a character development moment for me, making me realise a lot about myself. That is why I want to encourage students to try different roles and provide opportunities to not only explore acting, but every other possibility.

Each pre-service teacher’s voice hinted at drama as a transformative experience, personally and in terms of professional growth. They told us how the ideas explored in drama change in a wider human sense. But while many of these pre-service drama teachers identify that drama is broadly transformative, some seem less able to specify how. There are questions needing answers about how drama is transformative. Drama teacher education must move beyond vague mysticism and articulate clearly how and why drama is transformative.

What emerges here is that transformation is understood in multiple registers: personal growth (increased confidence, self-discovery), social awareness (critical engagement with issues like misogyny), and professional development (discovering leadership and organisational strengths). These narratives illustrate that pre-service teachers do not simply inherit the discourse of drama as transformative, they locate transformation in concrete experiences that shape who they are becoming as teachers.

At the same time, participants’ occasional vagueness underscores the challenge for drama teacher education to move beyond taken-for-granted claims of transformation and instead support pre-service teachers in articulating the processes through which it occurs. In doing so, their professional identity is shaped not only by experiencing transformation, but by learning to name, analyse, and facilitate it for their future students.

In summary, the themes discussed above suggest that pre-service drama teachers’ professional identities are formed through an interplay of passion and role models, experiences of safety and belonging, doubts and insecurities, and the perceived notion of the transformative power of drama. Each theme highlights not only what participants value in drama education but also how they locate themselves within it - as inheritors of inspiring legacies, as creators of safe spaces, as reflective practitioners negotiating uncertainty, and as facilitators of transformation. In this way, their motivations, memories, and concerns operate as resources for identity construction, revealing both the possibilities and tensions of becoming a drama teacher. These narratives therefore provide the foundation for understanding identity not as a fixed trait but as a process negotiated through inspiration, constraint, and the realities of professional life.

Discussion

This study asked how pre-service drama teachers’ motivations, memories, and concerns inform the construction of their professional identity. We now interpret the themes identified in the findings in relation to existing research and theory, highlighting both alignments and tensions. The perceptions of 22 pre-service drama teachers reveal that identity formation is a layered process, shaped by passion for the subject, remembered experiences of teachers’ past, and concerns about preparedness and legitimacy. Their stories both affirm existing research on effective drama pedagogy and highlight gaps in how initial teacher education supports the development of confident professional identities.

Motivations: Passion and Transformation

Motivations to become drama teachers were grounded in a conviction that drama can be transformative. Participants described drama as a space for self-discovery, belonging, and personal growth. Natalie explained that “Drama provides students with an opportunity for transformation,” while Stella described drama as a “safe place” for exploring identity. Such accounts echo broader claims for drama’s aesthetic, psychological, and social impact (Chinyowa, 2009; Nicholson, 2005; Taylor, 2003; Thompson, 2006), Greene’s (1995, 2010) concept of aesthetic education as a catalyst for imagining new ways of being, and Gadja’s (2016) framing of drama as identity reconstruction through aesthetic and liminal experiences.

Yet, transformation cannot be assumed. While many spoke with conviction, others, such as Amy, expressed ambivalence, reminding us that drama does not guarantee change for all learners. In line with Nicholson’s (2005) caution, we position transformation not as inherent to drama but as a possibility shaped by pedagogical, relational, and contextual conditions. This framing avoids romanticisation and directs attention to the mechanisms through which transformation may occur.

These expectations also sit uneasily alongside participants’ recognition that drama often lacks legitimacy in schools. Pre-service teachers spoke of drama’s promise but struggled to articulate how it works, reflecting the field’s tendency to assume rather than theorise transformation. Here, teacher education has a critical role. As Pascoe (2022) argues, learning to teach drama requires not only technical skill but an embodied, experiential, and socially grounded understanding of how drama itself is learned. Drama can open spaces for transformation, but it can equally reproduce disengagement or discomfort. Beginning teachers must therefore be equipped to navigate this variability with conceptual tools that enable them to sustain, defend, and critically reflect on drama’s value.

Memories: The Influence of Role Models

Memories of their own drama teachers, both inspiring and flawed, played a pivotal role in shaping participants’ emerging identities. Zac highlighted the influence of role models on his career aspirations, while Bea linked her choice to teach drama directly to the passion her teachers modelled. This reflects Lortie’s (1975) notion of the “apprenticeship of observation,” where memories of schooling shape conceptions of teaching, as well as McLauchlan’s (2011) finding that students perceive the most effective drama teachers as those who balance subject expertise, pedagogy, and interpersonal care.

Participants’ memories align closely with frameworks of effective drama teaching. Wright and Gerber (2004) emphasise engagement, risk-taking, empowerment, and advocacy as hallmarks of strong practice, and Gray and Lambert (2019) include supporting social-emotional development and authentic relationships. Our participants’ recollections of teachers who built trust, inspired passion, or, conversely, failed to connect, reveal how these qualities become internalised benchmarks, informing their sense of what it means to “be” a drama teacher. Such memories also signal early entry into wider communities of practice (Wenger, 1998), where professional identity is shaped not only through individual reflection but through participation in collective traditions of drama teaching.

Concerns: Preparedness and Legitimacy

While motivated by passion and inspired by memories, participants expressed significant concerns about their readiness for the demands of teaching. Mica worried about sustaining student engagement, Rona identified gaps in theoretical knowledge, and Bea admitted to imposter syndrome. Beau’s reflection was especially striking, revealing palpable tension between aspiration and self-doubt. His account underscores how vulnerable pre-service teachers can feel when entering a profession where expectations often outpace experience. These doubts highlight that identity formation is not a straightforward process but one marked by conflict, hesitation, and uneven confidence. As Beauchamp and Thomas (2009) argue, teacher identity is dynamic and contingent, shaped as much by uncertainty as by conviction. Recognising such insecurities is important to avoid portraying beginning drama teachers as following a single, overly romanticised trajectory.

Concerns also extended to systemic issues. Participants voiced anxiety about drama’s marginalised status within the curriculum, describing it as “second-tier” (Peta) or “marginalised” (Anita). This aligns with longstanding critiques of the precarious position of the arts in schooling (Bamford, 2006; Gray et al., 2017). The juxtaposition is telling - the same pre-service teachers who described drama as life-changing also acknowledged its contested legitimacy within schools. Their professional identities are thus shaped by this push and pull, between drama’s transformative promise and its institutional vulnerability. For teacher education, the challenge is to address these tensions directly by preparing future drama teachers not only with classroom strategies but also with the confidence and advocacy skills needed to sustain the subject in challenging contexts.

Identity-in-Process

Taken together, these findings demonstrate that beginning drama teachers’ professional identities are constructed through a dynamic interplay of motivations, memories, and concerns. Identity emerges not as a fixed state but as an ongoing negotiation between personal passion, remembered practice, and perceived challenges - echoing Pascoe’s (2022) view that learning drama and learning to teach drama are recursive, embodied processes. It is in the tension between romanticised ideals of drama’s transformative power and lived experiences of marginalisation that identity work becomes most visible. Participants are learning to hold both belief and constraint, inspiration and contestation. In this sense, drama teacher identity is inseparable from transformation. Pre-service teachers are becoming educators who must balance inspiration with marginalisation as part of their professional formation. Indeed, the very process of becoming a teacher requires navigating contradiction, developing resilience, and reconciling passion with constraint.This process reflects Wenger’s (1998) notion of identity as negotiated within communities of practice, as pre-service drama teachers begin to situate themselves within the professional networks and collaborative cultures that will sustain their future careers.

Implications for Pre-service Drama Education

These findings signal the need for pre-service drama education to engage more deliberately with the forces that shape identity. Programs can draw on students’ motivations, memories, and concerns as resources for reflective practice, while also embedding established frameworks of effective drama teaching (Gray & Lambert, 2019; McLauchlan, 2011; Wright & Gerber, 2004) as aspirational models. Ensemble-based and experiential approaches (Pascoe, 2022) remain vital for ensuring that pre-service teachers experience drama as both an art form and a pedagogy. At the same time, teacher education must emphasise that drama’s transformative potential is conditional rather than universal, equipping graduates to recognise when transformation occurs, when it does not, and how to foster environments that make it more likely. Crucially, teacher education must also prepare graduates to navigate the subject’s marginalised status, helping them reconcile passion with systemic realities and develop the confidence to advocate for drama’s place in schools. In doing so, drama teacher education can graduate practitioners who are pedagogically skilled, theoretically grounded, and resilient ambassadors for the transformative potential of drama (Daza et al., 2021; Gray et al., 2017).

Epilogue

They crowd into Theatre Sixteen, the final day of their drama teacher education course, the room alive with energy - half excitement, half nerves. The end has arrived quickly and slowly all at once. They’ve juggled coursework, placements, jobs, and the pressure of making it all work. Now, they’re here, on the edge of what comes next.

There’s laughter, the usual teasing and dramatic gestures. Phones come out for selfies and group shots, and they gather for a final class photo, one more image for the course coordinator’s door. But under the noise and movement is a quiet awareness: they’re stepping out of the familiar rhythms of university life and into theatre spaces where they will take the lead. The same way their teachers once challenged and inspired them, they are now ready to do the same for others. Not perfectly. Not all at once. But with purpose.

This moment captures not just the end of their training but the threshold of their professional identities. These pre-service drama teachers are stepping into a world where drama education holds profound transformative potential for students, yet where the subject often struggles for recognition. Their stories remind us that becoming a drama teacher is not a linear journey but a negotiation between passion, memory, and concern, lived out in the tension between transformation and marginalisation.

If initial teacher education programs are to prepare graduates who can thrive in this contested space, they must go beyond technical preparation to nurture reflective, resilient, and advocacy-oriented practitioners. Attending to pre-service teachers’ motivations, memories, and concerns provides a framework for doing so, revealing what future teachers bring with them, what sustains them, and what unsettles them.

In this sense, the voices of these participants are not only a snapshot of a cohort at the cusp of their careers but also a call to action. Drama teacher education must be intentional in transforming idealism into sustainable practice, equipping teachers to articulate drama’s value and defend its place in schools. At the same time, we must resist assuming that transformation is automatic; drama offers the possibility of change, but its impact depends on context, pedagogy, and relationships.

The stories and evidence gathered in this research has stimulated our interest in exploring further how drama transforms. For now, these stories offer both caution and hope. Caution that passion and good intentions alone are not enough, and hope that with the right preparation, a new generation of drama teachers can carry forward the discipline’s transformative promise while navigating its contested realities with integrity and resilience.