General Introduction

Creativity constitutes a fundamental competency in the 21st century and is recognised as a crucial curriculum objective across all educational levels (OECD, 2019b, 2019a, 2023). Recent research underscores the inextricable link between the arts and the cultivation of creativity (Beaulieu, 2022). Distinct from other domains such as science and business, the arts thrive by actively pursuing innovation through creativity, defined by ‘novelty’ in contrast to established practices. Conversely, scientific disciplines tend to preserve established knowledge while embracing new ideas, as illustrated by the principles of correspondence during paradigm shifts (Cropley, 2018).

In this context, puppet theatre is both an autonomous artistic medium and an effective pedagogical tool within educational settings (Jurkowski, 2009). It draws upon methodologies and principles from various art forms, notably visual and performing arts, as well as theatre and drama (Dabs & Sandweg, 2018; Paroussi & Lenakakis, 2023; Tizzard-Kleister & Jennings, 2020).

In a theatre or drama educational workshop, where puppets are perceived either as objects for play or as animated entities, unique multisensory learning and life experiences are facilitated for young children (Joss & Lehmann, 2016; Korosec, 2013; Lenakakis & Paroussi, 2019). The puppet serves as a medium through which children can explore and articulate emotions, such as fear, helping them understand and navigate their expansive environments. Furthermore, this experience allows children to reflect upon their identities, recognise the uniqueness of their facial expressions and broaden their self-concept (Dunn & Wright, 2015; Harris, 2021; Lenakakis et al., 2022).

This research explores the role of puppet theatre in educational drama as a means to nurture and inspire creativity in preschool children. This study aims to contribute to the ongoing discussion about the importance of empirical research in promoting awareness and support for applied puppetry (Amsdem et al., 2022), a significant aspect of applied theatre and drama. There is still a noticeable shortage of research that utilises quantitative methodologies in the fields of applied theatre and puppetry; this study aims to fill that gap. Our findings suggest that incorporating quantitative methods, particularly within mixed methodologies, fosters a productive conversation that highlights the value and impact of puppetry in educational settings. Previous research has also explored similar themes through quantitative approaches (Lenakakis et al., 2022).

Moreover, these investigations have disclosed a decline in puppetry as an educational resource, particularly as the focus shifts from early childhood education. It has been observed that educators frequently encounter challenges in observing and assessing the competencies children develop through puppetry, both independently and in collaboration with instructors. The essential skills of movement and orientation, explicitly included in nursery school curricula, appear insufficient compared to the complexities of animating inanimate objects.

One may postulate that nursery school educators often do not recognise these advanced skills due to insufficient training in their identification and evaluation, or they may undervalue these competencies as overly simplistic or “childish,” resulting in their dismissal. In light of these insights, teacher education programs must address these issues, especially in an era where the prioritisation of competencies and skills over mere content knowledge is emphasised as a primary educational outcome on a global scale (Lenakakis et al., 2022).

Continuing the dialogue on the significance of puppetry within an educational framework, this research endeavours to examine, investigate, and substantiate the correlation between puppetry and creativity, while offering targeted strategies for effectively integrating these concepts. Ultimately, it encourages researchers and educational practitioners to persist in their investment in the field. Specifically, this study aims to motivate drama and early childhood educators to create enriching experiences through the arts and puppetry for their students and themselves.

Literature review

Creativity is intricately connected to imagination, innovation, problem-solving, and divergent thinking. However, its complex nature makes defining it challenging (Jordanous & Keller, 2016). We can describe creativity as a process of addressing problems, discovering solutions, and producing valuable work through imagination, originality, and fluency (Harvey & Berry, 2023; Lloyd-Cox et al., 2022; Said-Metwaly et al., 2022). Its importance is undeniable on cultural, social, and economic fronts, and as such, it has been integrated into educational objectives worldwide (OECD, 2019a, 2023; Plucker et al., 2011).

In the 21st century, nurturing creativity is a key aim of formal education. It is essential in the arts and many aspects of daily life (Lenakakis & Paroussi, 2019; Paroussi & Lenakakis, 2023). Research indicates that creative learning encourages students to engage actively, seeking more profound, enduring knowledge, and is easier to cultivate than rote memorisation (Beaulieu, 2022; Plucker et al., 2011). The business sector thrives on innovation to sustain growth, while government bodies require individuals capable of forward-thinking and creative inspiration. Industries, the sciences, and various fields increasingly demand originality, imagination, flexibility, and new, applicable ideas. Today’s social and economic complexities necessitate innovative solutions that are adaptable enough to foster ongoing growth (Beaulieu, 2022; Robinson, 2017).

Moreover, creativity is increasingly recognised as a vital skill within information systems development teams (Ciriello et al., 2024), enhancing entrepreneurial capabilities (Wach & Bilan, 2023). Creativity becomes a prerequisite for encouraging behavioural change in modern contexts where sustainability solutions are sought (Saleh & Brem, 2023).

Research shows that while creativity is natural, it can only fully blossom when nurtured by favourable environments and practical methods (Hammershoj, 2014; Lubart & Guignard, 2004; Smogorzewska, 2014; Tuttle, 2020). That is why early childhood education should incorporate teaching materials, language, experimentation, play, exploration, and interaction to help foster problem-solving and the expression of new ideas in a process-driven rather than outcome-driven way (Isbel & Raines, 2003; Mullet et al., 2016; Runco & Jaeger, 2012). Four-year-olds exhibit a natural creativity that is best encouraged and developed at this early stage (Craft et al., 2012; Cremin & Chappell, 2021). However, as children progress into formal education, their thinking becomes more conventional and rational, which may lead to a decline in creativity. The educational system typically prioritises producing academic knowledge over encouraging creative thought (Harris, 2021; OECD, 2019b; O’Reilly et al., 2022). This emphasis on reproduction often clashes with creativity, which tends to suffer as children enter school (Lenakakis et al., 2022). To maintain order in large classrooms, teachers frequently stifle spontaneity, a key element of divergent and creative thinking (Dababneh et al., 2010; Robinson, 2017). Teachers often face the tough decision of whether to allow divergent thinking or to restrain it in the name of introducing the discipline of science, potentially reducing the vibrancy of the learning process by overlooking the significance of creativity in the arts (Lenakakis et al., 2022; Paroussi et al., 2023).

There has been a growing interest in updating and innovating teaching practices through creative methods in recent years. One area that has emerged in these discussions is the use of the arts, particularly drama and puppetry, which foster productive cross-disciplinary collaborations. These practices extend the often-limited boundaries of traditional education, uncovering innovative ways to enrich the learning process using the aesthetic resources that drama (White et al., 2021) and puppetry (Hannigan & Ferguson, 2021; Paroussi & Lenakakis, 2023) provide.

Research indicates that creativity exercises for five- and six-year-olds significantly benefit their convergent and divergent thinking skills, enhancing their performance quality (Alfonso-Benlliure et al., 2013). In a study involving 60 preschoolers in Malaysia, researchers implemented a 12-session creativity training program with an experimental and a control group. The experimental group participated in activities such as brainstorming, storytelling, web-based tasks, and role-playing. Creativity was measured using the Torrance Test of Creative Thinking (TTCT), with both pretests and posttests administered. Findings showed a significant increase in creativity scores in the experimental group, while no significant change was observed in the control group (Zahra et al., 2013). Similarly, a study in Ankara found that 40-year-olds engaged in a drama program demonstrated noticeably higher levels of creative thinking than a control group. The researchers measured creativity using the Torrance TCT-DP Test for Creative Thinking-Drawing Production before and after 24 interventions over 12 weeks (Yaȿar & Aral, 2012).

Puppetry and performing arts, in general, are rich fields for nurturing and expressing creativity (Thomson & Jaque, 2017). The playful nature of puppetry serves as an excellent medium for exercising creative behaviour, fostering communication, and encouraging collaboration. While a puppet may be just a toy, it also catalyses a child’s imagination, which, -in turn, fuels their creativity (Tselfes & Parousi, 2015).

Alongside STEAM education and Design Thinking, which have become popular in kindergartens to boost creativity (Lage-Gómez & Ros, 2024; Xie, 2023), drama should be recognised as a powerful context for nurturing creative thinking and action through what some scholars describe as Dramatic Thinking—a mode of cognition that integrates imagination, emotion, and embodied engagement within fictional scenarios (Davis, 2017). Findings from a longitudinal study of 127 children indicate that greater involvement in realistic role-play at age five, including puppet theatre, was positively associated with higher creative thinking scores in early adolescence. Observations and assessments of five-year-olds during role-play—using various toys and puppets—were followed up when they reached 10 to 15 years old to evaluate their creativity through the TCT-DP and the Alternative Uses Measure (Mullineux & Dilalla, 2009).

In research with six-year-olds, Lenakakis and Loula (2014) discovered that puppetry enhanced creativity in written expressions and elevated the quality of language lessons. Similar findings were reported by Hui et al. (2015) in their study on promoting language creativity through an annual arts program in Hong Kong. Additionally, qualitative research based on observations by nursery teachers (Luen, 2021) suggested that puppetry workshops could significantly enhance creative thinking and imagination in preschoolers. However, a gap remains in research concerning the link between puppet theatre and creativity in early childhood.

Teachers can generally engage children in puppetry creation from the ground up. This procedure involves crafting a simple story idea and making puppets and props, allowing children to partake in an educational play that nurtures their creativity and artistic skills (Hamre, 2012). To further enhance creativity, nursery teachers often find it beneficial to guide children in using materials by limiting their expressive choices, allowing them to concentrate on the artistic aspect. At this stage, the multi-arts nature of puppet theatre becomes evident as it integrates elements from the visual and performing arts, as well as applied theatre. As children invent simple stories or scenarios for their puppets to act out, they often unlock their imaginations and shed their inhibitions, such as concerns about how they will look or sound. This encourages them to approach their narratives and characters boldly, thereby enhancing their dialogue, cooperation, communication, and critical and creative thinking skills (Patterson, 2015). Through this playful engagement with materials and roles, children visualise concepts, explore their surroundings, experiment, and learn about the properties of objects and the world’s symbolic meanings. They actively feel, sense, and engage in play, which is widely recognised as a crucial element of embodied learning (Dunn & Wright, 2015).

Mottweiler and Taylor (2014) corroborated this by employing two creativity measurement instruments with four- and five-year-olds, which revealed a consistent positive correlation between role-playing and creativity. Conversely, Fehr and Russ (2016) found that while their experimental group experienced no significant enhancement in creativity following a brief role-playing intervention, the relationship between role-play and divergent thinking, a facet of creativity, still warrants further investigation, particularly with extended interventions.

Sowden et al. (2015) examined the impact of improvisation on various art forms, including acting, which pertains to the focus of our research on puppetry improvisation. Their study concluded that improvisation has a positive influence on divergent thinking and creativity in primary school students. Martinez and Fernandez-Rio (2021) explored the relationship between theatrical improvisation and motor creativity in secondary education, noting that students engaged in theatrical improvisation classes demonstrated significantly improved fluency, originality, and flexibility compared to peers in traditional educational drama classes devoid of improvisational elements. This argument supports the assertion that improvisation is vital for fostering creativity, consistent with our findings.

Recent research by Griniuk (2021) further affirms that participation in performing arts activities catalyses substantially creative development among children aged 6 to 13, broadening their imaginative and creative expressions. Stutesman et al. (2022) investigated how 21st-century skills and creativity can be further developed through drama classes for students aged 5 to 18, observing significant enhancements in creativity over successive semesters. However, they also noted that stricter grading protocols instituted by teachers over time resulted in declining creativity levels. That highlights the importance of drama classes in fostering student creativity, a notion supported by recent studies on younger children (Yildirim & Çetin, 2022), documenting statistically significant improvements in life skills such as creative thinking and problem-solving resulting from 12-week creative drama interventions. The findings suggest that extended interventions and a higher programming frequency are essential and in alignment with the current research.

In both drama and theatre pedagogical practices, combining dramatic play and improvisation creates a safe environment that nurtures sensory development and prepares children for the animation of puppets. Elements of improvisation, free expression, and creativity through role embodiment are fundamental components of educational drama (Anderson & Dunn, 2013; Neelands & Goode, 2015).

Methodology

Research objective and questions

This research investigates how participating in a puppetry workshop influences creativity among preschoolers. Our principal research question asks whether puppetry can enhance creativity in four- and five-year-old children. From this question, we formulated the following one-way research hypotheses:

Η1: Children’s creativity in the experimental group will improve after the intervention.

Η2: After the intervention, the experimental group will display higher creativity scores than the control group.

In this study, puppetry −as a form of spectacle and hands-on activity− is our independent variable, while children’s creativity is the dependent variable.

Sampling and Research Constraints

Our sample comprised 24 preschoolers split into two groups of 12. The control group did not participate in the intervention and followed the nursery’s standard curriculum, whereas the experimental group engaged in the puppetry workshop. All participants were enrolled in a state nursery school in Athens. The Greek education system is divided into three main levels: the first level includes preschool and primary education for children aged 4 to 5 and 6 to 11, respectively. The second level features a Gymnasium for students aged 12 to 15 and a Lyceum for ages 15 to 18, with each level spanning three years of study. Both primary education and Gymnasium are mandatory. In the experimental group, we conducted the intervention as explained in the following section (Mills & Gay, 2019).

Research method

This study employed a mixed-methods approach that integrates the advantages of both qualitative and quantitative research methodologies. This approach allows for the expansion and enhancement of quantitative findings through qualitative insights, thereby ensuring methodological triangulation and reinforcing the validity and reliability of educational research. In this context, subjects are not mere numerical units but individuals whose behaviours require interpretation (Mertler & Charles, 2010). To further validate qualitative data analysis, data triangulation was undertaken using multiple data collection methods, including participatory observer’s daily reports, recordings, videos, photographs, and documentation of children’s handicrafts, in addition to intervention reruns (C. Robson, 2002).

The action research was conducted by a research team member who serves as a nursery teacher. At the same time, academic colleagues provided general supervision following the ethical guidelines outlined by the University’s Research Committee. This cyclical process consists of four stages that can be repeated systematically. It commences with a reflection on the researcher’s inquiry and the desired areas for improvement. That is followed by formulating an action plan to foster progress and address the inquiry. The action stage implements new teaching practices while the teacher-researcher collects data pertinent to the actions undertaken, evaluating their impact on the desired outcomes. The final stage, reflection, entails an assessment of the action plan and any necessary adjustments to the cycle based on observations and data analysis (Cohen et al., 2017; Llego, 2022).

A quasi-experimental design was employed, which included both pretest and posttest assessments. In this design, the control group was not exposed to intervention, which is typical in educational research (Cohen et al., 2017). The designation “quasi” indicates that the sample is non-random, limiting the generalizability of the quantitative research findings (Maciejewski, 2010).

Research Tools

Torrance’s Thinking Creatively in Action and Movement (TCAM) test was utilised for quantitative data collection to assess the parameters of originality, fluency, and imagination—key components of creative thinking. The test was translated from English into Greek and back-translated into English, ensuring accuracy, and responses were organised alphabetically for easy referencing. Three of the four activities/trials are designed to measure originality and fluency (Activity 1: In how many ways? Activity 3: In which other ways? Activity 4: What can you do with a paper cup?). According to the user’s manual (Torrance, 1981) and the accompanying scoring tables, responses are assigned scores ranging from 1 to 3 based on their statistical infrequency. Responses not included in the tables receive a score of 3 for originality, whereas choreographic combinations of multiple movements can receive a score of 4. Fluency is evaluated based on the variety of responses provided for Activities 1, 3, and 4. The second activity (Can you move like a?) assesses imagination, with each of its six questions graded on a scale from 1 to 5, where 1 indicates no movement, and 5 denotes a perfect imitation. Both groups’ TCAM test measurements were conducted before and after the intervention.

Qualitative data were gathered through participatory observation, the observer’s daily reports, documentation of children’s handicrafts, videos, photographs, and recordings obtained with parental consent.

The programme – Reflective Action

The intervention program consisted of one session per day over six cycles, totalling six weeks. Following the completion of the third cycle, a determination was made to extend the initial plan, which initially included three cycles. Each intervention began with introductory games intended to stimulate imagination and concentration and concluded with relaxation and evaluation activities. Five interventions were scheduled per week, resulting in thirty sessions overall; the children’s prior engagement influenced each session’s duration. Activities were permitted to extend into the following class hour when necessary. To facilitate creativity, additional time was systematically allocated whenever the children required it or when the specific demands of the intervention necessitated such flexibility (S. Robson, 2012). All activities were conducted in a pleasant, playful, and secure environment, as the researcher assumed the role of the nursery teacher for the class.

During the first cycle, the focus was on exploring the children’s prior knowledge, establishing objectives, mapping planned actions, and introducing the Akatamakata programme, which involved the researcher portraying “Little Miss Akatamakata” and conducting a hidden treasures game. The children experienced their initial interaction with various puppets, constructed their puppet theatre from a cardboard box, and engaged in improvisation with any puppets they wished to explore. They also viewed a performance by the researcher, during which joint decisions were made regarding the rules of puppetry.

In the second cycle, the children created puppets using assorted materials, assigned identities to them and continued daily improvisations with their creations and those provided by the researcher. The children once again viewed a performance by the researcher.

Introductory games encompassing voice, discourse, body movement, and hand-and-finger coordination exercises began the third cycle. The acquisition of language skills was emphasised as it enabled children to express themselves more creatively, while the physical exercises facilitated puppet manipulation. The children were encouraged to develop stories in pairs; however, it was observed that groupings of three hindered collaboration, resulting in parallel rather than synchronised performances. Consequently, the programme was adapted to accommodate the children’s innate desire for improvisation, which manifested fluency, originality, and imagination. An additional three cycles concentrating on improvisation were integrated into the plan.

Throughout the initial three cycles, observations indicated that some children would leave their seats to approach the puppets during improvisational activities. Furthermore, puppeteers often spoke too quietly, leading to audience disengagement during extended performances. This feedback prompted a reiteration of the established guidelines, and the researcher monitored improvements in puppetry techniques, vocal projection, and the complexity of improvisational scenarios.

In the fourth and fifth cycles, the intensity of voice, discourse, and body exercises increased, with improvisation occurring in pairs while other participants observed. It was noted that when children transitioned from audience members to puppeteers, their vocalisation became better pronounced, and adherence to the established rules improved. Enhanced performance quality and more intricate narratives likely contributed to these developments.

During the sixth cycle, improvisation persisted during the first two days; on the third and fourth days, the children evaluated the programme, culminating in distributing participation awards to all participants.

Quantitative research results

TCAM test data were codified and subsequently entered into a database. Given its extensive range of applications, IBM SPSS Statistics 26 was selected as the most suitable statistical analysis software for this study. The analysis incorporated inferential statistics to address the research questions posed. The predetermined statistical significance level was set at p=0.05.

The Shapiro-Wilk test for data normality was also employed (Shapiro & Wilk, 1965). To evaluate our first research hypothesis concerning the effect of our intervention on creativity, the Shapiro-Wilk normality test was conducted on the fluency, originality, and imagination scores of children in the experimental group before and after the intervention. The results indicated that the variables conformed to a normative profile, except for the originality scores recorded before the intervention (p=0.045).

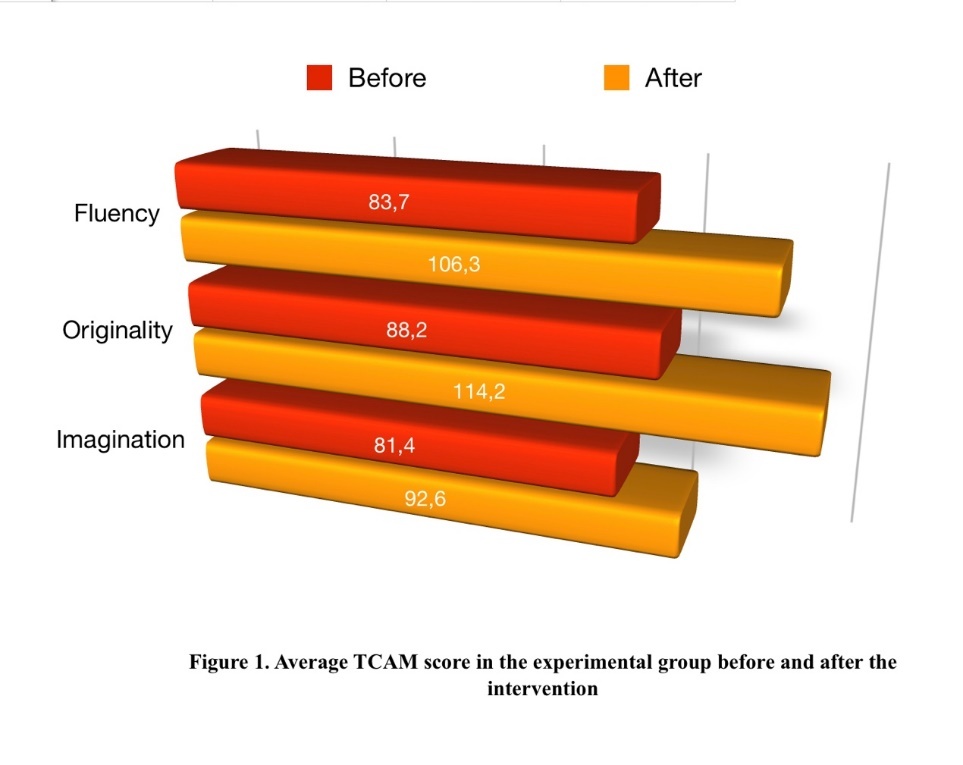

The paired-sample t-test revealed a statistically significant difference in the experimental group’s fluency and imagination scores. The average fluency score prior to the intervention was 83.7 (±10.5), which increased to 106.3 (±16.3) following the intervention, demonstrating statistical significance (t=-6.084, df=11, p<0.01). Similarly, the average imagination score improved from 81.8 (±16.1) to 92.6 (±20.8), also indicating statistical significance (t=-5.844, df=11, p<0.01), as illustrated in Tables 1 and 2.

The Wilcoxon test (see Table 2) revealed a statistically significant difference in originality before and after the intervention. Before the intervention, the average originality score was 88.2 (±15.2), which increased to 114.2 (±15.9) afterwards, demonstrating a significant change (Z=-3.210, p<0.01). Additionally, there was a noteworthy increase in overall creativity, with the t-test showing t=-19.81, df=11, p<0.001, indicating a shift in scores from 84.5 (±12.3) to 104.3 (±15.6) in the experimental group (see Table 1).

As illustrated in Figure 1 below, scores for fluency, imagination, and originality in the experimental group improved following the intervention. Statistically significant differences were found in all three categories before and after implementing the intervention.

To address our second research hypothesis, we conducted a normality test for fluency and originality in both the experimental and control groups after the intervention. The results indicated that fluency and originality did not conform to a normal distribution before the intervention, whereas post-intervention data showed a normal distribution only for imagination. Given this, we applied the Mann-Whitney test for fluency and originality comparisons between the experimental and control groups, as the normality condition was unmet.

The findings demonstrated a statistically significant difference in fluency between the two groups, with the experimental group achieving a mean rank of 15.75 compared to 9.25 for the control group (U=33.0, p=0.024<0.05). Furthermore, there was a significant difference in originality as well, with the experimental group scoring a mean rank of 15.71 versus 9.29 for the control group (U=33.5, p=0.024<0.05) (see Table 3).

An independent samples t-test was conducted for imagination. The average imagination score after the intervention for the control group was 86,6 (±16,2) and 92,6 for the experimental group (±20,8) (Table 4), with no statistically significant difference (t=-0,788, df=22, p=0,44>0,05) (Table 5).

In conclusion, a statistically significant difference was observed in the parameters of fluency and originality between the experimental group and the control group; however, this was not the case for the imagination parameter.

Qualitative research results

Qualitative data analysis was carried out using the thematic analysis method, which is particularly fitting when dealing with diverse data forms (Christodoulou, 2023). To uncover instances of creativity during our interventions, we undertook data entry and coding for our qualitative research, aiming to align the parameters of imagination, originality, and fluency with the TCAM test as closely as possible despite the complexities surrounding the definition of creativity.

Imagination was noted (following TCAM’s second activity) whenever the children conjured up, described, or acted out anything that did not exist, using their bodies or puppets—like saying, “Here we are on our island,” even when no island was in sight.

We recorded instances of originality in the children’s words, actions, or ideas in several contexts:

-

After TCAM’s first activity, they discovered unique ways to move or animate their puppets for a specific purpose, such as when a puppet “leans forward to show that she is sorry.”

-

Following TCAM’s third activity, if they coined inventive ways to label something, like describing a ribbon as “a uniform even a volcano cannot burn,” or if they created new words altogether.

-

After TCAM’s fourth activity, they used everyday objects in unusual ways, such as using a pencil sharpener as “food.”

Fluency was assessed per TCAM’s activities 1, 3, and 4, focusing on the frequency and quantity of creative ideas and acts under the umbrellas of imagination and originality.

We noticed some patterns through our thematic analysis of the coded instances of creativity from the twelve children in the experimental group and after comparing the frequency of these manifestations during our interventions. The five children who initially scored high in creativity demonstrated significantly more originality and fluency over time, while their imagination seemed to decline. Conversely, three of the seven children who began with low creativity became more original and fluent but also showed reduced imaginative skills. The remaining four children remained unchanged, including two with selective mutism and two with diffuse developmental disorder.

Notably, changes in creativity primarily emerged through improvisation during the final three cycles, where assessment and reflection took place. The children consistently sought to improvise, often changing names and plots when invited to act out their stories with their puppets. This lively improvisational element spurred even greater creativity. In addition to the parameters of fluency, originality, and imagination assessed by the TCAM test, qualitative observations revealed broader expressions of creativity throughout the intervention. These included enhanced linguistic creativity (e.g., inventive naming, metaphorical language), mathematical creativity (e.g., pattern recognition and symbolic reasoning during puppet story construction), as well as collaborative creativity and non-verbal expressive communication, particularly evident during improvisational puppet performances and interactions with the audience. These emergent forms of creativity point to the multidimensional impact of puppetry in early childhood education.

Discussion and Conclusion

The results of the quantitative and qualitative analyses derived from our action research indicate that the experimental group participants who attended the puppetry workshop exhibited a statistically significant enhancement in creativity compared to the control group, specifically regarding originality and fluency. In contrast, no significant change was noted in imagination. It is plausible that the extended six-week intervention, which included five sessions per week for 30 interventions, alongside a puppetry improvisation focus aligned with the children’s preferences, contributed to these results. Although some improvement in imagination was observed, it did not reach statistical significance, potentially since this aspect of creativity may necessitate more diverse activities of greater complexity or a format that allows for increased freedom and agency among the children.

Qualitative data further supports the validity of the quantitative findings, illustrating that children who initially demonstrated creative abilities became even more creative following the interventions. Notably, there was a marked exception: a young girl from a different country, who began with a low creativity score and limited linguistic expression, significantly progressed in originality and creativity, particularly in improvisation.

These results resonate with previous research linking dramatic role-play to creative performance. For instance, Mottweiler and Taylor (2014) identified a strong, positive correlation between role-play and creativity in preschoolers using two distinct creativity assessment instruments. Similarly, Mullineux and DiLalla (2009) demonstrated that early role-play behaviour—including puppetry—predicted creative ability in adolescence, reinforcing the idea that early dramatic engagement holds long-term developmental value.

Our findings diverge, however, from Fehr and Russ (2016), whose short-term role-playing intervention did not yield significant creativity gains. This contrast underscores the importance of duration and continuity: our own extended intervention may have provided children with more opportunities to internalise and apply creative behaviours, a factor echoed in Yildirim and Cetin (2022), who found statistically significant improvements in creative thinking and problem-solving after a 12-week drama intervention in preschool education.

Creativity is a multidimensional concept encompassing imagination, innovation, problem-solving, and divergent thinking (Jordanous & Keller, 2016). Although it may arise naturally in early childhood, research has demonstrated that creativity requires favourable environments and intentional pedagogical strategies to fully flourish (Lubart & Guignard, 2004; Runco & Jaeger, 2012). As a 21st-century educational objective (OECD, 2019a, 2023), creativity is increasingly considered essential for equipping students with the originality and flexibility required to meet complex social, cultural, and economic demands (Beaulieu, 2022; Saleh & Brem, 2023). Within this context, drama-based pedagogies and object animation—such as puppet theatre—emerge as particularly promising tools (Hannigan & Ferguson, 2021; Thomson & Jaque, 2017). Our findings confirm that when puppetry is infused with improvisational techniques, it serves as a rich site for creative development.

Qualitative analysis further underscored the role of improvisation in catalysing creative expression. Children constantly revised narratives, reimagined characters, repurposed objects, and explored unexpected storytelling paths. These patterns align with the findings of Sowden et al. (2015), who emphasised improvisation’s positive impact on divergent thinking, and Martinez and Fernandez-Rio (2021), who noted improvements in fluency, originality, and flexibility among students participating in improvisational theatre.

However, the observed decline in imagination among some participants may reflect internalised expectations or a developing awareness of “correct” creative responses. This phenomenon echoes findings from Stutesman et al. (2022), who noted that grading practices in drama education can inhibit creativity over time, suggesting that an overly structured or evaluative approach may suppress spontaneity and imaginative exploration.

The use of puppetry, when paired with expressive freedom and sensitive scaffolding, creates an optimal environment for cultivating creativity in preschool settings. This finding is consistent with research by Lenakakis and Loula (2014) and Hui et al. (2015), who demonstrated that creative dramatics enhance linguistic expression, collaboration, and cognitive flexibility. Moreover, the process of designing and animating puppets engages visual, auditory, kinesthetic, and symbolic modalities, offering a multisensory learning experience (Dunn & Wright, 2015; Hamre, 2012). Puppet theatre uniquely combines elements of visual and performing arts, storytelling, improvisation, and symbolic play. As children invent stories, develop characters, and manipulate objects in expressive ways, they transcend conventional roles, fostering communication, confidence, empathy, and critical and creative thinking (Patterson, 2015; Tselfes & Parousi, 2015).

These findings align with broader literature asserting that creativity must be actively fostered in early education before it is diminished by formal schooling’s tendency toward conformity and knowledge reproduction (Harris, 2021; OECD, 2019b; Robinson, 2017). When drama is implemented as a process-oriented rather than product-oriented activity, it supports embodied learning and offers space for divergent thought to flourish (Anderson & Dunn, 2013; Neelands & Goode, 2015).

This study supports calls for integrating sustained, arts-based interventions—particularly puppetry and improvisational drama—into early childhood education. Such practices not only promote fluency and originality but also foster the cognitive flexibility and communicative capacities essential for creativity in later life. Future research could explore longer-term interventions, consider age-based differences in the imaginative dimension, and investigate how teacher practices and classroom dynamics either constrain or amplify creativity. Ultimately, recognising dramatic play not simply as entertainment but as a serious pedagogical tool may help ensure that creativity is preserved, developed, and celebrated across educational contexts.

In summary, as a performing art form, this study suggests that puppetry can enhance creativity among preschoolers aged 4 to 5, showing a pronounced impact on originality and fluency, while no statistically significant effect was observed in the domain of imagination. Additionally, puppetry improvisation is more effective than standardised performance formats in promoting these creative outcomes.